We really have everything in common with America nowadays, except, of course, language.

Oscar Wilde

The King’s English is not the King’s. It’s a joint stock company, and Americans own most of the shares.

Mark Twain

We should have a great fewer disputes in the world if words were taken for what they are, the signs of our ideas only, and not for things themselves.

John Locke

We all live in a small unique world, that’s why we need at least one sole common language.

Carl william Brown

Language forces us to perceive the world as man presents it to us.

Julia Penelope

The quantity of consonants in the English language is constant. If omitted in one place, they turn up in another. When a Bostonian “pahks” his “cah,” the lost r’s migrate southwest, causing a Texan to “warsh” his car and invest in “erl wells.”

Author Unknown

English is a funny language; that explains why we park our car on the driveway and drive our car on the parkway.

Author Unknown

The goal of American English speakers appears to be to rob the mother tongue of direct meaning and replace it with needlessly-complex jargon.

Stewart Stafford

England and America are two countries separated by the same language.

George Bernard Shaw

I learned English by going to America and marrying an Englishman who didn’t speak French. That helped.

Catherine Deneuve

American English, English spoken in the United States. It differs from English spoken elsewhere in the world not so much in particulars as in the total configuration. That is, the dialects of what is termed Standard American English share enough characteristics so that the language as a whole can be distinguished from Received Standard (British) English or, for example, Australian English.

The differences in pronunciation and cadence between spoken American English and other varieties of the language are easily discernible. In the written form, however, despite minor differences in vocabulary, spelling, and syntax, and apart from context, it is often difficult to determine whether a work was written in England, the United States, or any other part of the English-speaking world.

The American lexicographer Noah Webster was among the first to recognize the growing divergence of American and British usages. His American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) marked this difference with its inclusion of many new American words, indigenous meanings attached to old words, changes in pronunciation, and a series of spelling reforms that he devised (-er instead of British -re, -or to replace-our, check instead of cheque). Webster went so far as to predict that the American language would one day become a distinct language. Some later commentators, notably H. L. Mencken, compiler of The American Language (3 vol., 1936-48), have also argued that it is a separate language, but most authorities today agree that it is a dialect of British English.

Patterns of American English

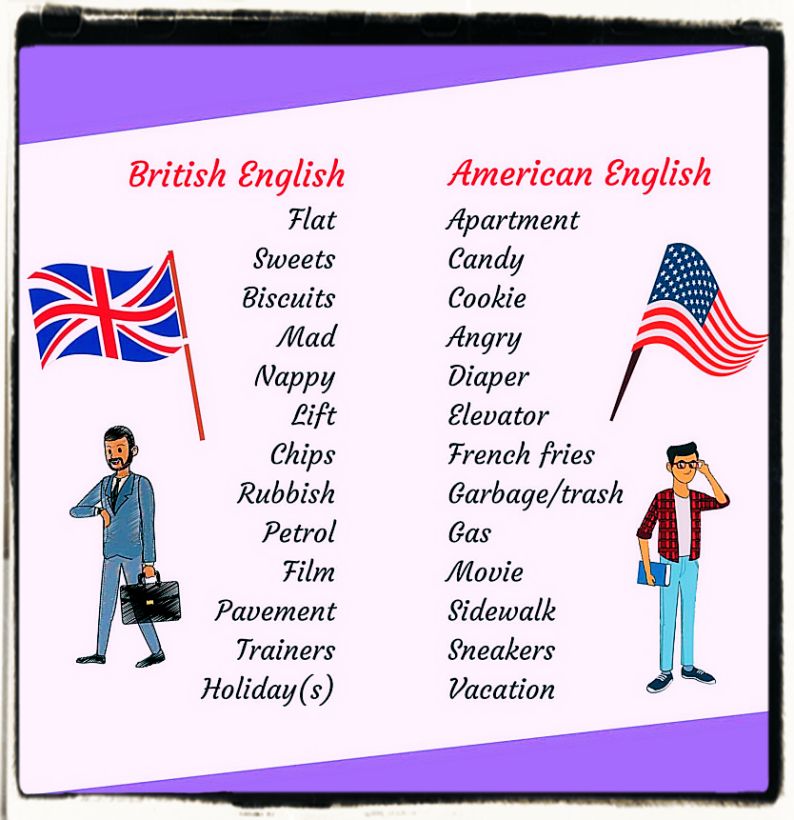

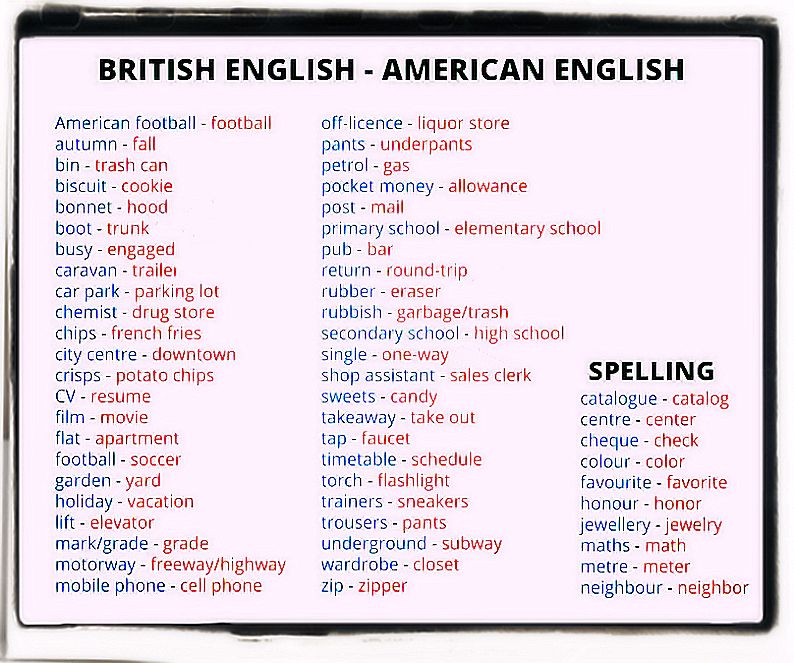

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the study of American English was concerned mainly with identifying Americanisms and giving the etymologies of Americanisms in the vocabulary: words borrowed from Native American languages (mugwump, caucus); words retained after having been given up in Great Britain (bug, to mean insects in general rather than bedbug specifically, as in Great Britain); or words that developed a new significance in the New World (corn, to designate what the British call maize, rather than grain in general). Large numbers of American terms (elevator, truck, hood [of an automobile], windshield, garbage collector, drugstore) were shown to differ from their British counterparts (respectively: lift, lorry, bonnet, windscreen, dustman, chemist’s). Such lexical differences between Standard American and British English still exist; but as a result of modern communications, speakers of English everywhere have no trouble in understanding one another. More recently, linguistic researchers have turned their attention to the study of variation patterns in American English and to the social and historical sources of these patterns.

Regional Dialects

Regionally oriented research before 1940 distinguished three main regional dialects of Standard American English, each of which has several subdialects. The Northern (or New England) dialect is spoken in New England and New York State; one of its subdialects is the “New Yorkese” of New York City. The Midland (or General American) dialect is heard along the coast from New Jersey to Delaware, with variants spoken in an area bounded by the Upper Ohio Valley, West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and eastern Tennessee. The Southern dialect, with its varieties, is spoken from Delaware to South Carolina. From their respective focal points these dialects, according to this theory, have spread and mingled across the rest of the country.

Social/Cultural Dialects

Social/cultural dialects vary both the vocabulary and grammar of Standard American English and are not always intelligible to speakers of the standard language. The most distinctive variety of American English, in terms of vocabulary and grammar, is the social/cultural dialect known as Gullah, actually a contact language, or creole, spoken by blacks in the Georgia-South Carolina low country, but also as far away as southeast Texas. Gullah, combining 17th- and 18th-century Black English and several West African languages, has given to American English such words as goober (peanut), gumbo (okra), and voodoo. It is the dialect used in the novel Porgy (1925) by the American writer DuBose Heyward. “Me beena shum” (I was seeing him/her/it) is barely intelligible to a speaker of Standard American English, and almost all Gullah speakers shift to more standard usage when conversing with outsiders.

Pennsylvania Dutch, another distinguishable dialect, is actually English heavily influenced by literal translations from the original German language of settlers in Pennsylvania. In this dialect such a construction as “He may come back bothsides, ain’t?” (He might come back on either side, mightn’t he?) is possible. Most Pennsylvania Dutch speakers also readily adapt themselves to standard usage.

Black English

Until the 19th century, most blacks throughout the country spoke a creole similar to Gullah and West Indian English. Change in the direction of Standard American English vocabulary and syntax, particularly in the 20th century, has been rapid but never complete; the Black English of the inner cities characteristically retains such locutions as “He busy” (He is busy) as opposed to “He be busy” (He is busy indefinitely) and “She been said that” to express action markedly in the past (she had said that). In the 1960s Black English became a topic of linguistic controversy in educational circles because of its supposed deficiencies and ultimately was the subject of legislative action under the Bilingual Education Act (1968). Nevertheless, Black English has made its own rich contributions to American English vocabulary, especially through jazz—from the word jazz itself, to such terms as nitty-gritty, uptight, and O.K. The last, now thought to be of African origin, is also the Americanism most widely diffused throughout the world.

Development of American English

English commentators in the 18th century noted the “astounding uniformity” of the language spoken in the American colonies, excepting the language spoken by the slaves. (Subvarieties of English, however, were spoken by Native Americans and other non-British groups.) The reason for this uniformity is that the first colonists came not as regional but as social groups, from all parts of England, so that dialect leveling was the dominant force.

Grammatical Formality

Against this background of uniformity, deviations from Standard American English have frequently met with disapproval from those who promulgate “correct” English. Grammatical formality is the most notable feature of Standard American English, and particular stigma is attached to the use of nonstandard verb forms. Rigidity in grammar and syntax in written Standard American English is greater than in British English in part because large numbers of immigrants acquired English as a second language according to formal rules. Also, social mobility in the U.S. has produced certain anxieties and confusion about “correct” usage as an indication of status. What is considered Standard American English is today spoken for business and professional purposes by people in all parts of the country, many of whom speak very differently in private. In writing, however, many feel constrained to use formal, Latinate locutions even when addressing close friends.

Regional Variations

In earlier times, the dialect of New England, with its British form of pronunciation (ah for a in path, dance; loss of the r sound in barn, park), was considered prestigious, but such pronunciations failed to inspire nationwide emulation. Indeed, no single regional characteristic has ever been able to dominate the language. (One of the reasons that some linguists define Black English as a language rather than a dialect is that its vocabulary, pronunciation, and syntax are similar in all parts of the country, rural and urban.)

Today, the concept of so-called Network Standard, promoted by radio and television, provokes some argument from dialectologists, who champion diversity and richness of speech; but regional variations have by no means been obliterated. The Midland (or General American) distinct r sound persists (car), and even educated speakers in the South do not differentiate pen from pin.

Growth of the American Vocabulary

The uniformity of the English spoken by the British colonists to about 1780 was soon disrupted by non-English influences. First, many Native American words were taken over directly to describe indigenous flora and fauna (sassafras, raccoon), food (hominy), ceremonies (powwow), and, of course, geographic names (Massachusetts, Susquehanna). Phrasal compounds, translated or adapted from the Native American, were also added to English: warpath, peace pipe, bury the hatchet, fire water. Other borrowings came in time from the Dutch (boss, poppycock, spook), German (liverwurst, noodle, cole slaw, semester), French (levee, chowder, prairie), Spanish (hoosegow, from juzgado, “courtroom”; mesa, ranch[o]; tortilla), or Finnish (sauna).

Other modifications in vocabulary came about presumably because of lack of education or because of confusion on the part of explorers and settlers who applied incorrect names to things encountered in the New World – for example, partridge, used indiscriminately for quail, grouse, or other game birds, and buffalo, applied to the American bison.

American English vocabulary has been and still is enriched with jargon, terms coming from trades and professions. The social sciences, law, and the academic disciplines in particular are accused of contributing gobbledygook (an Americanism referring to verbal obfuscation). Slang, argot, and even certain euphemisms have also been a constant source of language enrichment, although some terms die out before they are admitted to the standard vocabulary. In the 19th century prudishness influenced the language; legs were called “limbs,” and pregnant “in the family way.” Similarly, in the 20th century, Americans, in their reluctance to confront reality, have coined such euphemisms as “senior citizen” or “golden ager” for old people and “nursing home” for old folks’ home and poorhouse.

As might be expected in a nation originating from 13 maritime colonies, a great admixture of nautical expressions has been in the language since early times: freight (used as a verb), slush fund, shove off, hail from. Baseball took over skipper (to mean manager), on deck, and in the hole (originally hold) from the nautical vocabulary and contributed many of its own colorful idiomatic expressions to the general language (for example, get to first base).

Influence on British English

Spread by motion pictures, books, and television, Americanisms—especially American slang—have in large numbers found their way to Great Britain, more and more blurring the distinctions between the two forms of the English language. Although nonstandard phrases, such as “met up with” or “try out” (in the sense of test), may still encounter objections from purists, the very force of their objections shows how influential such words have been on everyday British English speech.

Joey Lee Dillard