Irish modern history and the character of the people who live in Ireland, the Emerald Isle.

At the start of the 19th century, Irish soldiers formed a considerable proportion of the British army, and by 1830, there were more Irish than English soldiers in the army. Irish regiments served in many parts of the world, and also had a role in maintaining law and order in Ireland. Ireland became one of the first parts of the United Kingdom to have a police force, when Sir Robert Peel set up the Peace Preservation Force (PPF) in 1814. The four provincial areas of the County Constabulary were merged to form the Irish Constabulary in 1836, and Queen Victoria honoured the police with the title “Royal Irish Constabulary” (RIC) in 1867, partly in recognition of their role in suppressing a rising by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

The Napoleonic wars caused a boom in the Irish economy and an increase in the value of exports. However, the end of the war in 1815 brought a corresponding slump in prices. A crisis in the woollen industry in England in 1825 led to goods being sold at ruinous prices, accelerating the decline of the woollen industry in Ireland. The cotton industry in Ulster failed to keep up with trends towards steam weaving, and by 1838, only 6 cotton mills were left in Belfast. However, wet-spinning of flax had been introduced in Belfast and mass produced linen was able to compete successfully in the textile market. By 1842, the railway line from Belfast had been extended to Portadown, and the Victoria channel had been cut to make the port much more suitable for large ships.

Competition from the cotton industry pushed down the wages of weavers in rural areas. In the 1841 census, over half of the families in Ulster fell into the poorest category, which included agricultural labourers, impoverished weavers and holders of farms of less than five acres. The failure of the potato crop in 1845 and 1846 brought tragedy to families already living on the edge of subsistence, in spite of the efforts of local relief committees, the government and charities. In 1847, diseases such as typhus and relapsing fever claimed more victims. It is estimated that over 200,000 people (about 9% of the population) died in Ulster as a result of the potato famine, and about the same number emigrated.

This century saw the rise of modern Irish nationalism, with the Catholic Association, led by Daniel O’Connell, campaigning first for the removal of the remaining Penal Laws (1829) and then in the 1840s for repeal of the Union with Great Britain. O’Connell had a horror of violence; a horror which was not shared by groups such as the IRB in Ireland and the Fenian Brotherhood in America. In the last two decades of the century, Charles Stewart Parnell and the other Irish nationalist MPs made an alliance with Gladstone, leader of the Liberal party. This resulted in two Home Rule Bills being introduced at Westminster in 1886 and in 1893.

“No man has the right to set a boundary to the onward march of a nation. No man has the right to say: ‘Thus far shalt thou go, and no further'”

Charles Stewart Parnell, 1885

“If political parties and political leaders… hand over… the lives and liberties of the loyalists of Ireland to their hereditary and most bitter foes, make no doubt on this point;… Ulster will fight, and Ulster will be right”

Lord Randolph Churchill, 1886

In 1850, the Irish Tenant League was set up to call for a custom called “Ulster tenant-right” to be given the force of law. Many Protestant and Catholic tenant farmers joined the League campaigning for fair rents, free sale (actually a payment made by the new tenant to the previous tenant) and fixity of tenure. A number of Land Acts were passed at Westminster from 1870 onwards, culminating in the Wyndham Act of 1903. Landlords were encouraged (with a bonus) to sell entire estates when three-quarters of the tenants agreed. The Wyndham Act in particular brought about a revolution in land ownership, with millions of pounds being advanced by the government and paid back by tenants as land annuities over a period of 68½ years.

Even at the start of the century, there was little evidence of the radical Presbyterian politics that had been displayed during the 1798 rebellion. The Orange Order led the Protestant opposition to Home Rule, and the Grand Lodge encouraged Ulster Unionists to form the Anti-Repeal Union at Belfast in January 1886. At Westminster, Lord Randolph Churchill decided that Home Rule was the issue to topple Gladstone, and put his support behind the Anti-Repeal cause. As a result, the 1886 Bill was defeated by 30 votes in the House of Commons. Gladstone resigned and then lost the subsequent General election. A second Home Rule Bill in 1893 was defeated in the House of Lords, but the issue of the Union has dominated Ulster politics ever since.

There is an atmosphere in Ireland which is not like anywhere else in the world, and I’ve been round most of the world, and I still think it’s the most beautiful… well, I found out to my amazement that what people said about it being one of the most beautiful countries in the world is true, it is extraordinarily beautiful. And it has an extraordinarily beautiful quality of life possible there… destroyed by the political aspirations of the few.

I’ve been asked merely because you’re Irish and because occasionally you have to admit to that, “What’s the cause of the Irish problem?” This has been going on now for five hundred years. It’s a world of history in itself to say “What is the cause of the Irish problem?” Where it will end is an equally insoluble question.

David Coulter, TV director from Ulster

But I was brought up in a situation in Derry, which was my home town, where you knew, from your earliest possible moments of consciousness, whether you were a Catholic or a Protestant. That was one of the first things you ever knew. There is this phrase about cradle bred hatred’, and it’s very real. It’s a very real thing. It’s a knowledge of an enemy.

I suddenly saw this child, about eight to ten, little fellow, coming hobbling down with one leg, towards me. And he came down and he sat down beside me and started to chat, and I said “How are you?” and he said, “Oh, I’m all right now.” And I said “Oh good, well what… what was the problem?” and he said. “Oh. I had my leg blown off” And I said “Oh, I’m very sorry to hear that.” and he said “Sorry? What are you sorry for? Sure I’m a hero of the revolution now.”

As the remarks of the Irishman David Coulter indicate, Ireland is a complex and troubled country, or more accurately, two countries, probably the most difficult of all the English speaking countries to explain or understand. A grasp of the Irish character is something that has eluded foreign observers for centuries and it has been said that the Irish also remain incomprehensible to the Irish themselves. This is probably the result of an extremely complicated history which has left such a strong mark on the land and its people, and a mixed heritage that leads to the question ‘Who, in fact, are the Irish?’

Basically there are three categories of Irishmen today: firstly the indigenous Irish, or Celtic Irish. who are staunch Roman Catholics and make up the vast majority of Eire, or the Republic of Ireland. and the minority of Ulster, also known as Northern Ireland, which is, as everyone knows, one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. A second group is often referred to as Anglo Irish, the products of centuries of intermarriage and a cultural mix with England.

These Irishmen have always been Anglican Protestant and represent a small but highly significant minority. Thirdly, there are the Loyalists or Scotch-Irish who are strongly Calvinist Presbyterian Protestant and are roughly two-thirds of the population of Ulster. It is their differences, religious, political, social and economic, and their historical relationship to the British Crowh that is the cause and the key to the turmoil on this divided and often unhappy island.

The Celts are said to have come to Ireland in about 200 B.C. and were pagan until the arrival of the missionary St. Patrick, who converted them to Christianity which they adopted with a zeal unsurpassed in any other Christian country. James Joyce referred to Ireland as being “priest-ridden” and another Irish writer,Edna O’Brien, calls it “God-ridden”. Certainly Ireland today is the staunchest adherent of the Church of Rome and the Celtic Irish have always equated the Catholic faith with nationalism.

It was the Irish Celts who, during Europe’s Dark Ages, kept alive Christian teaching and formal learnine of all kinds. In fact. from the 5th to the 9th centuries Ireland was the storehouse of Western civilisation which Irish scholars and missionaries then had to reintroduce to the barbarian continent of Europe. Although the Celtic Irish have for the most part been a poor peasant people, they have always had a high regard for literature and Latin and Greek culture. As a people they can be cruelly vindictive, passionate, fanatical, but endowed with a rich humour that gives comic relief to their obsessions with religion, martyrdom, death and violence.

Two IRA gunmen were detailed to assassinate a British general. They were to shoot him as he passed a certain crossroads. So they waited and they waited and they waited and he didn’t turn up, so one of the gunmen turned to the other and he said: “I don’t think he’s going to turn up. I hope nothing has happened to the poor old soul”. Irish joke

Like the Celts of Scotland, the Celtic Irish are famous for their great love of drinking and fighting, both of which amount to something like a national sport. The very name of an Irish family who lived in London, known for their brawling and battling, provided the English word “hooligan” which has now become international to describe unruly and riotous behaviour.

But otherwise the temperament of the Irish Celts is more like that of Southern Italians or Sicilians than the dour Scots. They have never been an industrious people and if the Spanish are famous for putting off’ work until manana, in Ireland it’s tomorrow. God willing, preferring a pint of their national drink, Guinness stout, good conversation and a song in the pub to productivity.

In Dublin today, a businessman may conduct his affairs in a pub, spending as much time on blather as business. Blather is a typical Irish word for talking nonsense. Some of you may recall the Scottish proverb that makes a virtue of silence: “Give your tongue more holidays than your head.” The Irish tongue is never on holiday, for talking is what they do best and best like to do, whether the talk is of consequence or not. With the Irish, conversation is an art form and if it is amusing and entertaining, that is enough, for style is more important than content. In an Irish pub one can get as drunk on words as on Guinness, and this is doubtless the reason that Ireland’s greatest product has always been literature. Certainly Irish writers have contributed far more than their share to the vast stockpile of poetry, prose and drama written in the English language, and this joy of verbage is transformed to genius in the hands of a great writer like James Joyce.

He kissed the plump mellow yellow smellow melons of her rump, on each plump melonious hemisphere, in their mellow yellow furrow, with obscure prolonged provocative melonsmellonous osculation.

from Ulysses by James Joyce

Yes when I put the rose in my hair like the Andalusian girls used or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will yes.

from Molly Bloom’s soliloquy, of Ulysses by James Joyce

Imagination is one of the most predominant qualities of the Irish and the rich folklore of the Celts is filled with it, along with heavy lacings of wild romanticism and superstition. The leprachauns small mythical shoe-makers, are well known all over the English speaking world, but the Irish also have a host of other fairies, little people, ghosts and imaginary beings that are said to roam the Irish countryside and populate their many legends. One of these, called Far Darrig, a giant of a man, is dedicated to playing practical jokes, especially gruesome ones, on poor peasants. One of his victims was a tinker, that is, a man who wanders from village to village mending pots and pans. This folk tale tells of the poor fellow’s experience at the hands of this legendary practical joker.

The Anglo Irish are, as the name implies, products of mixed breeding and a dual cultural heritage. For historical reasons this Protestant minority have always been the landowners and aristocracy of Ireland. Although the life style of the Anglo Irish is similar to the English gentry, and prominent families like the Guinnesses who own the famous brewery can and do move between the two worlds of Dublin and London with equal ease, this is not to say that the Anglo Irish are not loyal Irishmen. Indeed they have often been the fiercest fighters for Irish home rule and were largely responsible for the surge of Irish nationalism and the so-called Celtic revival and took an active part in the events which led to the separation of Southern Ireland from Great Britain.

The Irish writer Brendan Lehane writes that it was the Anglo Irish, not the Celtic Irish, that supplied almost all the greatest figures in Irish literature, art and architecture, and certainly the literary list is impressive: Jonathan Swift, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Oliver Goldsmith, Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, John Millington Synge and the poet William Butler Yeats, to name only the more internationally famous. Swift, author of the famous Gulliver’s Travels, can be called the most powerful and savage satirist in English, and wrote what must be one of the most biting pieces of black humour as a solution to Ireland’s poverty and distress”:

A Modest Proposal.

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked or boiled, and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout. I do therefore humbly, offer it to public consideration, that of the hundred and twenty thousand children, already computed, twenty thousand may be reserved for breeding. That the remaining hundred thousand may at a year old be offered in sale to the persons of quality and fortune, through the kingdom, always advising the mother to let them suck plentifully in the last month, so as to render them plump and fat for a good table. I grant that this food will be somewhat dear, and therefore very proper for landlords who, as they have already devoured most of the parents, seem to have the best title to the children. I have already computed the charge of nursing a beggar’s’ child (in which list I reckon all cottagers, labourers and four-fifths of the farmers) to be about two shillings per annum, rags included, and I believe no gentleman would be unwilling to give ten shillings for the carcase of a good fat child. The mother will have eight shillings net profit, and be fit for work till she produces another child. Those who are more thrifty (as I must confess the times require) may strip the skin from the carcase; which. artificially dressed, will make admirable gloves for ladies, and summer boots for fine gentlemen. As to our City of Dublin. slaughter houses may be appointed for this purpose, although I rather recommend buying the children alive, and dressing them hot from the knife, as we do with roasting pigs.

Jonathan Swift

The Anglo Irish strain and the introduction of the English language go back to Ireland’s first invasion from her neighbours across the Irish Sea in the 12th century, when, ironically, the English King Henry II was asked by a Celtic Chief to send a military force to help him make war on the Irish Prince of Leinster. The English stayed on and intermarried, and the course of history was set. The political events which followed fill volumes of books and the incredible tangle that is Irish history and its relationship with England for some 700 years cannot be simplified with anything approaching integrity. Indeed modern Irish historians, both Protestant and Catholic, are now finding that what has been presented to generations as Irish history is often distortion of the truth or pure fiction, used to support and justify religious and political prejudices on both sides.

It is, however, important to remember that although the Irish have been a relatively small problem in the sweep of English history. England has been the major problem throughout Irish history and the dominance of the English, both politically and culturally, has left the Anglo Irish in a difficult and uncomfortable position, not entirely Irish, if the Irish race is defined as Celtic Catholic, yet certainly not English either.

The division between these two cultures and religions greatly worried the nationalist Anglo Irishmen who wished to identify with the Irish peasant class, but were victims of their own Protestant backgrounds which looked down on the Catholic Celts as an inferior species. The great playwright J.M., Synge came from an upper class Anglo Irish Protestant family against which he rebelled. On the advice of Yeats, he went off to live with the peasants in the West of Ireland in order to write honestly and affectionately about them. However, when his masterpiece The Playboy of the Western World was first presented at Dublin’s famous Abbey Theatre, it was interpreted as disparaging the Irish people by portraying them as simple peasants and Irish Celtic nationalists caused riots in the theatre. None the less the play has endured as a great classic of modern Irish drama.

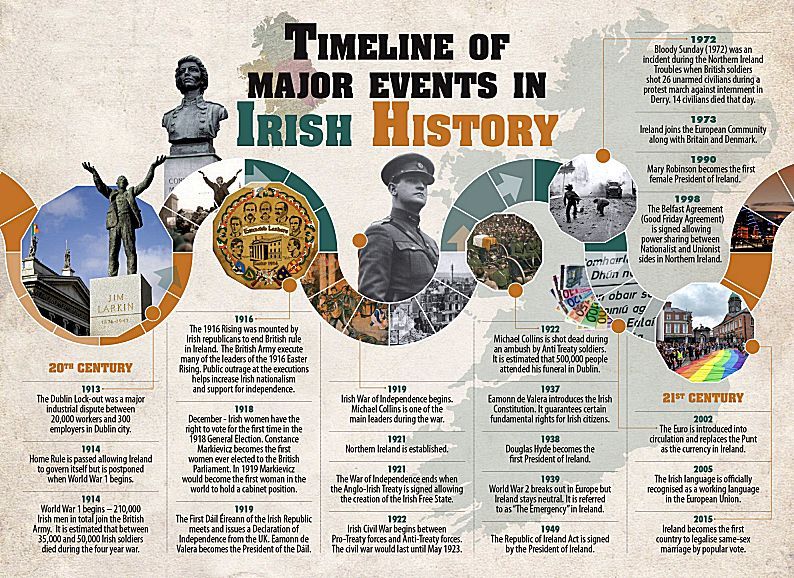

The most important event in modern Irish history was the Easter uprising of 1916, instigated by Patrick Pearse, a fanatical nationalist. Plans to give Ireland an independent government were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and two years later impatient Irish republicans staged an armed revolt in Dublin and proclaimed Ireland an independent republic. The rebellion was easily put down by the British forces, but after 15 of the rebels leaders, including Pearse, were executed for this open act of treachery during war time, the Irish republicans had the martyrs they needed to win Irish public sympathy for their cause. Yeats himself commemorated the event in one of his most celebrated poems, Easter 1916.

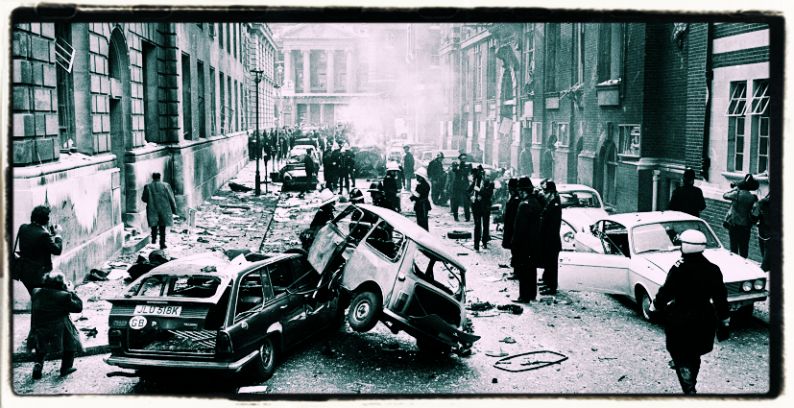

What had changed was Kathleen ni Houlihan, the personification of Ireland as a poor old woman, who had now put down her rosary and taken up a gun. The following five years, known as the “Irish troubles”, were filled with violence as the zeal for independence grew in the South of Ireland, matched by the Protestants determination not to be abandoned by Britain and ruled by a Catholic majority. Atrocities were committed on both sides as the IRA went into battle against the Black And Tans, a brutal force sent by Britain to suppress the rebellion. Shootings were followed by executions which stirred passions into more shootings and so it went on, with prison cells echoing songs celebrating martyrs: “Another martyr for old Erin another murder for the crown The British laws may crush the Irish But cannot keep our spirits down. Kevin Barry, Irish Rebel Song”.

As violence became commonplace, many nationalists like Yeats regretted their part in inspiring armed rebellion. Sean O’Casey also voiced disapproval of heroic violence at the expense of innocent people in his play The Shadow of a Gunman: “Seamus: I’ve a different opinion now when there’s nothing but guns in the country… and you daren’t open your mouth… But this is the way I look at it – I look at it this way: you’re not going – you’re not going to beat the British Empire – the British Empire, by shooting an occasional Tommy at the corner of an occasional street. Besides, when the Tommies have the wind up… when the Tommies have the wind up… they let bang at everything they see – they don’t give a God’s curse who they plug”… It’s the civilians that suffer; when there’s an ambush they don’t know where to run. Shot in the back to save the British Empire, and shot in the breast to save the soul of Ireland. I’m a Nationalist myself right enough – a Nationalist right enough, but all the same – I’m a Nationalist right enough; I believe in the freedom of Ireland, and that England has no right to be here, but I draw the line when I hear the gunmen blowing about dying for the people, when it’s the people that are dying for the gunmen! With all’ due respects to the gunmen, I don’t want any of them to die for me. The Shadow of a Gunman by Sean O’Casey.”

At the end of the Great War, the British, weary of the age-old conflict and bitterness, wanted to be rid of the Irish problem once and for all. Britain, however, found herself in what was to become a familiar position – trying to disengage from a colony where two opposing religious and ethnic groups are at each other’s throats -not unlike the situation in India, in Palestine and in Cyprus in later years. Under heavy pressure from the Protestants of Ulster, who were every bit as fanatical as the IRA and threatened a full civil war rather than accept political unity with the hated Catholic South, the British Parliament agreed to partition, and a treaty signed with representative politicians from Dublin provided for two separate parliaments – one in Dublin to rule 26 predominantly Catholic counties, and another in Belfast to rule the six predominantly Protestant counties, whose citizens chose to remain British.

So in 1921, independence finally arrived, but the violence did not stop by any means. The partitioning of Ulster (The name Ulster has several possible derivations: from the Norse name “Uladztir”, which is an adaptation of Ulaidh and tir, the Irish for “land”; or similarly it may be derived from Ulaidh plus the Norse genitive s followed by the Irish tir. It has also been suggested to have derived from Uladh plus the Norse suffix ster (meaning place), which was common in the Shetland Islands and Norway) was unacceptable to the Republicans and a new wave of bombings and shootings broke out – this time, not against the British, but against the elected government in Dublin. During the two years before independence, the British had executed 24 IRA rebels for terrorist crimes. During the following two years, the Irish government executed more than three times that number for the same reason.

The IRA today is as skilled at publicity and propaganda as it is at manufacturing and discharging bombs and its recent Hunger Strike campaign to establish political status for its convicted gunmen has kept it on the front pages of the world’s press and added greatly to its support and strength – a fact that worries no one so much as the Prime Minister of the Republic of Ireland, Dr. Garrett Fitzgerald: “I appreciate the IRA are a threat to our Government, to our democracy, and not a threat to Britain. It’s we who have to live with them, we who have to fight with them… fight them, it’s we who have to stand up to them and save democracy here, and we’ve often got very little help from British Governments which have at times negotiated with them. The fact is that the IRA have gained greatly in strength; their fund raising in America has risen sharply as a result of the way they have manipulated opinion In this regard, and the way they have been able to present British attitudes in this regard. That money buys guns, those guns kill people in Northern Ireland; they create greater tension there. All of that is dangerous and damaging and from our point of view the sooner the IRA’s gains can be wiped out and eliminated the better.”

The Northern Ireland Protestant majority is the result of the so-called plantation of Lowland Scotsmen some 350 years ago. These Celts from Scotland. many of whose ancestors had come from Ulster in the first place expelled the Irish Celts from their land and went hard to work to build up the farms and industries that make Ulster the most prosperous part of Ireland today. They brought with them their Calvinist Presbyterian faith as learned from John Knox, and have always supported unity with Great Britain. These Loyalists, or Orangemen as they are called because of their support for the Protestant succession of the British Crown, are none the less Irishmen too, but have a shameful record of religious bigotry and oppression of the Ulster Catholic minority.

David Coulter, a television producer who was born in Londonderry as his fellow Protestants call it, or Derry. as it is known to the Catholics, explains the differences between his type of Irishman and the Irish of the South: “They are as different as any two nationalities could be. The Southern Irish, with whom I have a great deal of sympathy, are people of great charm who are artistic and tend to tell a lie would hang you, but for the right reasons, they don’t want to offend you with the truth. The Northern Irish are people who are incredibly hard-working, horrendously clean and disgracefully honest. I mean they look at you straight in the face and tell you the truth. They’re a hard-faced lot of people. And they’re businessmen, and it’s not for no reason that there are first generation Northern Irish Presidents of the United States. They really are amazingly hard-working and strong people. But they have as much in common with the Southern Irish as they have with the Watusi”.

In Northern Ireland, even a simple sentimental melody has sectarian significance. This well known tune is called Danny Boy by the Catholics, and Londonderry Air by the Protestants, and has a different set of words which singers choose according to their background – even though neither set of lyrics has anything to do with religion per se. In addition to the religious and political differences between the North and the South of Ireland, there is a strong economic division, not unlike that between North and South Italy, which adds to the tension. In a recent opinion poll taken in Ulster, virtually all of the Protestants and a surprising 33% of the Catholics were against unification with the Republic, and wished to remain British. Yet 20% of the population want unification and an unknown number are prepared to continue a violent campaign to achieve that end. In 1969 sectarian violence reached such a peak that Britain was required to send a military force to maintain civil order. Was it a good idea? Here are the views of some Irishmen:

“At the time I don’t think they had any alternative, I think they should have been taken out sooner than they have been.” Howard Davies, Protestant from Eire

“No no. I don’t think they were right at all… to send troops in. I think that they should have left the Irish to themselves and let them sort it out.” Franchine Mulrooney, Catholic from Eire

“It’s difficult for me to be absolutely impartial about this because it happened that I was on holidays in 1969 in Derry, and we’d spent the night of August 12th sitting up dressed ready to leave home and take to the fields because the bombs were going off all over the town and the place was on fire. It looked like… it looked like Atlanta burning in Gone with the Wind. It was very very frightening. And the following morning the place was full of soldiers, and for that moment I felt Thank God, at least we have some sort of protection.'” David Coulter, Protestant from Ulster

Should the British soldiers be withdrawn from Northern Ireland? And if so, what would happen?

“Well I don’t see any political solution coming out of the situation with the troops being there, because it gives the IRA an enemy to fight and consequently there’ll just be violence. Perhaps if the British troops weren’t there, we cduld come to some .settlementm. I mean, they’ve been there long enough and nothing good has come out of it. I mean, technically speaking they’re wasting their time.”

Howard Davies

“Catholics probably would be glad if they were withdrawn, but still it wouldn’t solve the problem.”

Franchine Mulrooney

“There’s no guarantee that drawing out the soldiers out of Northern Ireland wouldn’t give rise to the biggest blood-bath there’s been in centuries. How does Britain look in the world scene if it does that? There has been a suggestion that U.N. forces could be put in there. But nobody in their right mind has suggested pulling out all the forces from the Irish situation It’s too dangerous. It’s far too dangerous.

David Coulter

In the past 12 years over 2,000 people have been murdered in Ulster for political motives – two-thirds of those being civilians. What possible solution is there for two opposing groups whose leaders, as of now, refuse to be in the same room together, much lessi” engage in useful talks? No doubt most people feel that ultimately unification is the answer, but who is able or willing to force 80% of a population to accept a solution they are set against?

“I see no reason why they should have any reason not to be unified if political arrangements were worked out.” Howard Davies

“I don’t really believe there is a final solution for Northern Ireland, The problem is something that’s deep down in the Irish blood, and I think the Irish temperament is something really even the Irish don’t understand themselves”. Franchine Mulrooney

“It’s a dilemma which I cannot begin to see how you solve. You have got to start so far back in the education of those already born, and go farther than that into the unborn in order to begin again… with this 500 years of grotesque history behind, which they love to drag up: it’s in song, it’s in drama, it’s in literature, and it’s in their day-to-day life. One of the things which you will definitely find if you go to the South of Ireland and start asking questions is that 90% of them want to know nothing at all about the North of Ireland. They would prefer you cut it off and toted it into the Atlantic and sank it. It’s just a damn nuisance’s”. David Coulter

But much as the British and the moderate Irish would wish, Ulster won’t just disappear; for Kathleen ni Houlihan is trapped in her own history, fantasies and illusions. Memories over the centuries of landlords, poverty, the potato famine when over a million starved and millions more were forced to emigrate, rebellions and battles. murders, executions, heroes, saints, traitors, bigots and fanatics, poets and politicians. A past that is the ever-continuing present.

“We envy the men of action Who sleep and wake. murder and intrigue Without being doubtful, without being haunted’ And I envy the intransigence of my own Countrymen who shoot to kill and never See the victim’s face become their own Or find his motives sabotage their motives. Up the Rebels, to Hell with the Pope, And God Save – as you prefer – the King or Ireland The land of scholars and saints: Scholars and saints my eye, the land of ambush, Purblind manifestoes, never-ending complaints, The born martyr and the gallant ninny’s; The grocer drunk with the drum, The land-owner shot in his bed, the angry voices Piercing the broken fanlight in the slum. The shawled woman weeping at the garish altar.

Kathleen ni Houlihan! And yet we love her for ever and hate our neighbour And each one in his will Binds his heirs to a continuance of hatred. Send her no more fantasy, no more longings which Are under a fatal tariff For common sense is the vogue And she gives her children neither sense nor money Who slouch around the world with a gesture and a brogue, And a faggot of useless memories. Extract from Autumn Journal XVI by Louis MacNeice, Ulster poet

1972 March

The Parliament of Northern Ireland is prorogued (and abolished the following year).

1973 1 January

Ireland joins the European Community along with the United Kingdom and Denmark.

1973 June

The Northern Ireland Assembly is elected.

1974 1 January

A power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive takes office, but resigns in May as a result of the Ulster Workers’ Council strike; the Assembly is suspended and later abolished.

1985 15 November

The governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom sign the Anglo-Irish Agreement.

1990 3 December

Mary Robinson becomes the first female President of Ireland.

1995

Ireland enters the Celtic Tiger period, a time of high economic growth which continues until 2007.

1998 April

The Belfast Agreement is signed; as a result, the Northern Ireland Assembly is elected, to which powers are devolved in 1999 and a power-sharing Executive takes office.

1999 1 January

Ireland yields its official currency, the Irish pound, and adopts the Euro.

2015 23 May

A 62% to 38% referendum result makes Ireland the first country to legalise same-sex marriage by popular vote.

About Ireland you can also read: