Italian influence on English, an article that explains the influence of the Italian language, culture and authors on the English language through the centuries.

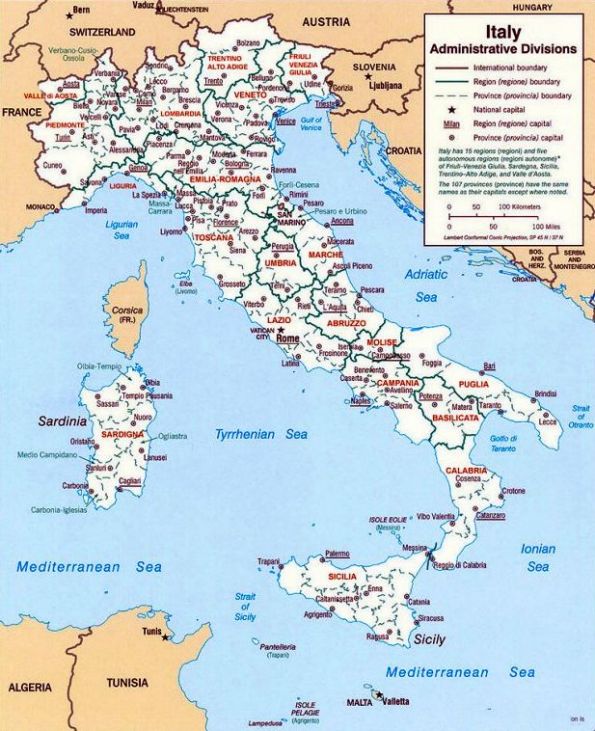

The Italian language is a Romance language spoken by some 66,000,000 persons, the vast majority of whom live in Italy (including Sicily and Sardinia). It is the official language of Italy, San Marino, and (together with Latin) Vatican City. Italian is also (with German, French, and Romansh) an official language of Switzerland, where it is spoken in Ticino and Graubünden (Grisons) cantons by some 666,000 individuals.

Italian is also used as a common language in France (the Alps and Côte d’Azur) and in small communities in Croatia and Slovenia. On the island of Corsica a Tuscan variety of Italian is spoken, though Italian is not the language of culture. Overseas (e.g., in the United States, Brazil, and Argentina) speakers sometimes do not know the standard language and use only dialect forms. Increasingly, they only rarely know the language of their parents or grandparents. Standard Italian was once widely used in Somalia and Malta, but no longer. In Libya too its use has died out.

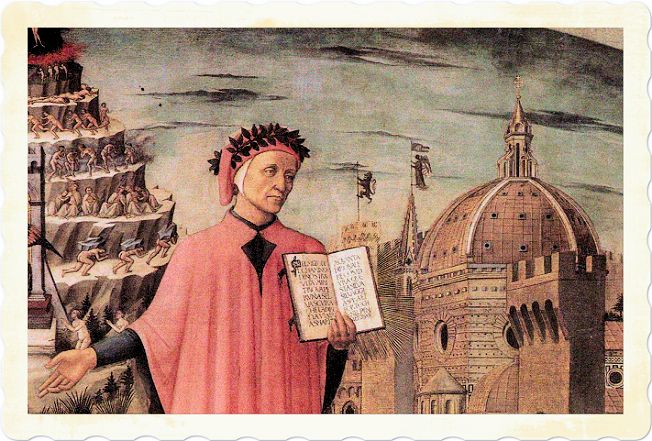

Dante, the main Italian poet, in exile about 1300, began a book meant to guide the development of Italian poetics. He dropped it after a few chapters, but what he finished of “De vulgari eloquentia” contains an explanation in medieval terms of the linguistic map of Europe.

In the introduction he begins by stating something obvious to him, and no doubt to his peers, but that might seem strange to us. In most of the world around him, he says, there are two languages in the same place. Call them “low” and “high,” or “vulgar” and “classical,” or “common” and “learned.” Dante calls the first “vulgar” or “vernacular.”

We moderns can miss something obvious to Dante: we study the language of Cicero and Caesar, and then assume French, Italian, and Spanish descended from that. They didn’t. They descend from the common speech of the people going about their lives in the Empire, the “Vulgar Latin,” which always was a separate thing from the artificial literary Latin.

Dante goes on to make a radical, revolutionary statement, by the way, but a necessary one for his purpose: he identifies the common speech as the more valuable, because the more human. Of these two kinds of language, the more noble is the vernacular: first, because it was the language originally used by the human race; second, because the whole world employs it, though with different pronunciations and using different words; and third because it is natural to us, while the other is, in contrast, artificial.

Geoffrey Chaucer, the renowned English poet of the Middle Ages, lived from approximately 1343 to 1400. While there is no direct evidence that Chaucer had personal knowledge of the main literary Italian authors of his time, he was certainly aware of Italian literature and its influence.

Chaucer’s most famous work, “The Canterbury Tales,” includes several stories and characters that are influenced by Italian literature. For example, his story “The Knight’s Tale” is based on the work of the Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically his work “Teseida,” which tells a similar story of love and chivalry. Chaucer also drew inspiration from Boccaccio’s “Decameron” for some of his other tales.

Additionally, Chaucer was familiar with the works of Dante Alighieri, particularly Dante’s “Divine Comedy.” Chaucer’s “The House of Fame” and “The Parliament of Fowls” show signs of Dantean influence.

So, while Chaucer may not have personally known these Italian authors, he was certainly aware of their works and drew inspiration from them, incorporating elements of Italian literature into his own writing. This reflects the broader trend of the influence of Italian literature on English literature during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

The Italian Renaissance had a significant influence on English language and culture during the 15th and 16th centuries. This period of intellectual and artistic revival in Italy had several notable impacts. Italian literature in particulary with works by authors like Petrarch and Dante, was translated into English and inspired English writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer. Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” was influenced by Italian storytelling techniques.

Italian humanistic ideas emphasizing the value of individualism, human potential, and classical learning influenced English scholars and thinkers. This led to a renewed interest in classical Greek and Roman texts, which shaped English intellectual discourse. Then Italian Renaissance art, characterized by realism and perspective, influenced English artists and architects. Renaissance ideas can be seen in English cathedrals, palaces, and paintings of the period.

In this period the English language absorbed many Italian words, especially related to art, music, and cuisine. Words like “piano,” “opera,” and “spaghetti” entered the English lexicon during this time. What’s more Italian Renaissance advances in science and exploration, such as developments in navigation and cartography, indirectly contributed to the growth of English exploration and the expansion of the English language.

Last but not least the Italian Renaissance’s political ideas, including the concept of the “Renaissance prince” as described by Machiavelli, influenced English political thought, contributing to discussions on monarchy and governance. In summary, the Italian Renaissance had a multifaceted impact on English language and culture, leaving a lasting imprint on literature, art, language, philosophy, and politics during this transformative period in history.

John Mullan explores how Italian geography, literature, culture and politics influenced the plots and atmosphere of many of Shakespeare’s plays. John Mullan is Lord Northcliffe Professor of Modern English Literature at University College London. John is a specialist in 18th-century literature and is at present writing the volume of the Oxford English Literary History that will cover the period from 1709 to 1784. He also has research interests in the 19th century, and in 2012 published his book What Matters in Jane Austen?

So frequent and thorough is Shakespeare’s engagement with Italy in his plays that it has been suggested that he travelled to Italy some time between the mid-1580s and the early 1590s – the so-called ‘lost years’ when we have no reliable information about his whereabouts. There is no evidence to support this claim, but it is clear that Italy was his primary land of the imagination. Unlike other countries – such as France, Austria or Denmark – in which he set particular plays, his representations of Italy are diverse and usually precise. Different cities in Italy are chosen for different plays and given distinct qualities and associations.

When he so often chose Italian settings for his plays, Shakespeare was exploiting his contemporaries’ lively interest in the country. It was the destination of many Elizabethan travellers and the subject of many travel writings. (In As You Like It, when Jaques tells Rosalind that he has the ‘humorous sadness’ of a ‘traveller’, she naturally assumes ‘you have swam in a gundello [i.e. gondola]’ (4.1.19–21). Any serious traveller would have been to Venice.) If Shakespeare did not know Italian, many of his educated contemporaries did. It is likely that he encountered educated Italians in London – he might well have known leading humanist scholar John Florio, an Italian who was tutor to his patron, the Earl of Southampton.

Italy had a special hold on poets. The very forms of Elizabethan verse and the terminology of its patterns (stanza, sestina) often came from Italy. The sonnet (from the Italian sonetto) was introduced to English in the 1550s in explicit imitation of Italian models, and especially of the Italian poet Petrarch. In Romeo and Juliet, a play whose very prologue is a sonnet, Mercutio, mocking Romeo for his lovelorn posturing, tells Benvolio to expect from him the poetry of unrequited passion: ‘Now is he for the numbers that Petrarch flow’d in’ (2.4.38–39). The 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca (known as ‘Petrarch’ in English) was greatly admired in England, especially for his sonnets, which elaborately expressed his hopeless love for the nearly divine ‘Laura’.

John Florio was an Italian-born linguist and scholar who played a significant role in influencing the English language through his works. His influence primarily stems from his contributions to English lexicography and his translations of Italian literature. In 1598 and in 1611 he published the first two Italian-English dictionaries: A World of Words, and Queen Anna’s New World of Words.

Unlike the lexicographers that preceded him, he didn’t use just Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch, but as a wide a variety of works as possible. This dictionary was a valuable resource for English speakers seeking to learn Italian and helped introduce numerous Italian words and phrases into the English language. It facilitated cross-cultural communication and enriched English vocabulary with terms related to art, music, literature, cuisine, and daily life.

This scholar also translated several Italian literary works into English, most notably the essays of Michel de Montaigne. His translation of Montaigne’s essays introduced English readers to Montaigne’s humanist philosophy and literary style, influencing English prose writing in the process. He is recognised as the most important humanist in Renaissance England.

John Florio contributed to the English language with 1,149 words, placing third after Chaucer (with 2,012 words) and Shakespeare (with 1,969 words), in the linguistic analysis conducted by Stanford professor John Willinsky. He was also the first translator of Montaigne into English, the first translator of Boccaccio into English and he wrote the first comprehensive Dictionary in English and Italian (surpassing the only previous modest Italian–English dictionary by William Thomas published in 1550).

Florio was also known for his playful and inventive use of language. He often incorporated puns, wordplay, and creative expressions into his writing. His linguistic experimentation contributed to the development of a more flexible and expressive English language.

Some scholars suggest that Florio’s translations and linguistic style may have inspired aspects of Shakespeare’s works, including the use of Italian words and phrases in Shakespearean plays like “Romeo and Juliet” and “Othello.”

On December 2020, Bbc aired a documentary titled “Scuffles, Swagger & Shakespeare: The Hidden story of English”, in which Dr John Gallagher uncovered the real, complex story of how English conquered the world. John Florio was there too, described as a man who wanted to bring European culture and literature to the English masses.

Gallagher reminded the audience that while in Italy and France a renaissance had been transforming art and literature, in England it had struggled to put down roots, and some thinkers were worried that the country was falling behind. But John Florio was determined to change that. He made his mission to bring continental ideas in England. Gallagher showed the difficulties that immigrants faced in Elizabethan England, by reading the words John Florio wrote in 1591: “I know they have a knife at command to cut my throat. An Englishman in Italian is a devil incarnate.”

Italian literature, and indeed standard Italian, have their origins in the 14th-century Tuscan dialect – the language of its three founding fathers, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. The thread of literature bound these pioneers together with later practitioners, such as the scientist and philosopher Galileo, dramatist Carlo Goldoni, lyric poet Giacomo Leopardi, Romantic novelist Alessandro Manzoni, and poet Giosuè Carducci.

Women writers of the Renaissance such as Veronica Gàmbara, Vittoria Colonna, and Gaspara Stampa were also influential in their time. Rediscovered and reissued in critical editions in the 1990s, their work prompted an interest in women writers of all eras within Italy.

Italian music has been one of the supreme expressions of that art in Europe: the Gregorian chant, the innovation of modern musical notation in the 11th century, the troubadour song, the madrigal, and the work of Palestrina and Monteverdi all form part of Italy’s proud musical heritage, as do such composers as Vivaldi, Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini, and Bellini.

Music in contemporary Italy, though less illustrious than in the past, continues to be important. Italy hosts many music festivals of all types – classical, jazz, and pop – throughout the year. In particular, Italian pop music is represented annually at the Festival of San Remo. The annual Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto has achieved world fame. The state broadcasting company, Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI), has four orchestras, and others are attached to opera houses; one of the best is at La Scala in Milan. The violinists Uto Ughi and Salvatore Accardo and the pianist Maurizio Pollini have gained international acclaim, as have the composers Luciano Berio, Luigi Dallapiccola, and Luigi Nono.

Contemporary productions maintain Italy’s eminence in opera, notably at La Scala in Milan, as well as at other opera houses such as the San Carlo in Naples and La Fenice Theatre in Venice, and the annual summer opera productions in the Roman arena in Verona. Tenors Luciano Pavarotti and Andrea Bocelli were among Italy’s most acclaimed performers at the turn of the 21st century.

As Michael Ricci explains in an article, Italian-American citizens have influenced both our language and our society. With the immigration of many Italians to our country, they not only have contributed to our language, but also to our culture. Words used in English that are borrowed from the Italian language are commonly known as loan words.

Our language contains many Italian loans words. These words encompass many areas of our society like food, music, architecture, literature and art, the military, commerce and banking. The Italian loan words are the most dominantly descriptive in the subject area of our foods. We are all familiar with pizza, ravioli, pasta, bologna (baloney), coffee, pepperoni, salami, soda, artichoke and broccoli, but the more discriminate gourmets might find many other foods and drinks found here to excite their palates.

Other delicious offerings are available at many choice Italian restaurants like panini, an Italian sandwich made usually with vegetables, cheese, and grilled or cooked meat. Ciabatta an open textured bread made with olive oil. Foccacia is a flat Italian bread traditionally flavored with olive oil and salt, and often topped with herbs and onions. Fish items are available like calamari, a squid prepared as food; or scampi, which are large shrimp boiled or sautéed and served in garlic and butter sauce.

Most people in our society who are not Italian-Americans refer to all kinds of macaroni as pasta; we Italian-Americans like to call them macaroni. Some macaronis are used with soup and are often given to infants because of their small size, like acite de pepe and pastina. Besides servings being given to babies, these are also used in soup. These small macaronis are sometimes used as toppings on salads. Other macaronis like spaghetti, linguini and ziti are cooked in seasoned tomato sauce. Manicotti is stuffed with ricotta or other soft cheeses. Lasagna is a favorite as a baked macaroni, which is layered with cheese, and ground beef baked between the sheets of precooked lasagna. Tortellini is a specialty pasta in small rings, stuffed usually with meat or cheese, and served in soup or with a sauce. Pesto is a tomato sauce consisting of, usually, fresh basil, garlic, pine nuts, olive oil and grated cheese.

Many of these meals are topped off with many delicate sweet foods like biscotti, crisp Italian cookies flavored with anise, and often containing almonds and filberts. Tiramisu is a dessert of cake infused with a liquid, such as coffee or rum. Tortoni is a rich ice cream often flavored with sherry. Amaretto is a sweet, almond-flavored liqueur. Maraschino is a bittersweet clear liqueur with marasca cherries.

Food words are only the tip of the Italian-American iceberg. Other Italian loan words can be found in music. By far, music seems a topic dominated by Italian loan words. The more familiar musical ones are alto, soprano, basso (voice ranges); cello, piano, cello, piccolo, viola, oboe, violin and harmonica (musical instruments); largo, andagiettio and fermata (musical tempos); crescendo, forte and sforzando (volume); agitato, bruscamente and affettuoso (mood); molto, poco and meno (musical expressions); and altissimo, acciaccatura and pizzicato (musical techniques).

Examples in the literature category are novel and scenario; in art, fresca (fresh painting) and dilettante (amateur); in architecture, balcony and studio; in banking, bank and bankrupt; military: alarm, colonel and sentinel; politics: ballot, ghetto and bandit. Italians formerly used balls in their voting, and the word “ball” eventually became “ballot.”

Many second-generation Italian-Americans, as well as integrating much of their language into ours, also contributed greatly to our culture. In the movie industry, Martin Scorsese excelled as a director, while Anne Bancroft (Anna Marie Italiano) starred as an actress in “The Helen Keller Story” and “The Graduate.” Frank Sinatra, who has been acclaimed as a great American pop singer, also achieved fame in the movies by winning an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in “From Here to Eternity.” He also shared the singing limelight with Tony Bennett (Benedetto), Madonna (Ciccone) and tenor Mario Lanza. Joe DiMaggio excelled as a New York Yankee baseball player, while Rocky Marciano was the boxing heavyweight champion who retired while still champion. Francesca Cabrini, now known as “Mother Cabrini,” was our country’s first canonized saint.

In politics, Samuel Alito was the first Italian-American to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court. Fiorello La Guardia served our country as the first Italian-American elected to Congress, and later served as mayor of New York City for three terms. LaGuardia Airport is named after him. Rudy Guiliani most recently also served as that city’s mayor, and acted as a quieting influence during the 2001 attack on the Twin Towers. Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman to receive a major political party’s nomination as vice president of the United States. Nancy Pelosi has been most prominent in recent years as a California representative, and later as the first female speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

As well as contributing to our language, Italian-Americans have become part of the patchwork of our culture. Learning about the many Italian loan words in our language and the contribution of many Italian-Americans are among the excellent ways that you can watch your language.

List of English Words of Italian Origin

As Michael Kwan writes, the Italian language has a profound influence on the English language, and hundreds of words qualify for the list of English words of Italian origin. Since so many words come from Italian, we will make the list a little less overwhelming by breaking the words down into categories. Since Italian food seems to be such a favorite of the American people, we will start there!

The word “ballet” originates in Italian

Food and Cooking

You’ll encounter many of these food terms both inside and beyond your local Italian restaurant!

al dente: literally “to the tooth,” meaning firm and slightly chewy (particularly pasta)

al fresco: outside in the fresh air

amaretto: almond-flavored liqueur

antipasto: appetizer course with olives, cured meat, artichokes and peppers

arugula: a type of slightly peppery, leafy vegetable

barista: originally a barman or bartender, now used for person who makes coffee at a cafe

biscotti: a type of cookie

bologna: a type of deli meat

broccoli: a variety of green vegetable

cappuccino: espresso with foamed milk

carpaccio: thinly sliced meat

ciabatta: type of Italian bread

espresso: strong, small coffee

focaccia: round, flat bread with herbs

fettuccine: ribbon style pasta

gelato: frozen dessert similar to ice cream

lasagna: a layered pasta dish

latte: coffee with steamed milk

linguine: a long, flat pasta

macchiato: espresso with a small amount of foamy milk

maraschino: a strong, sweet liquer often used with cherries

panini: Italian grilled sandwich

parmesan: a type of dry cheese

pasta: Italian style noodles

pepperoni: originally referring to bell peppers, now also used for hard, cured sausage

pesto: a type of green sauce made with olive oil and pine nuts

pizza: flat dough topped with tomato sauce, cheese, and other ingredients

polenta: a dough made with cornmeal

prosciutto: salted, cured ham sliced very thin

provolone: a type of cheese

salami: salted Italian sausage

scampi: large shrimp

spumoni: variety of Italian ice cream

tiramisu: Italian dessert with ladyfingers and coffee

tortellini: type of filled pasta

trattoria: Italian restaurant

tortoni: variety of ice cream

Music Vocabulary

With so many incredible composers and artists over the years, Italian culture and heritage has influenced music all around the globe.

allegro: played in a lively and brisk style

alto: a “high” male voice or “low” female voice

basso: a low, bass voice

bravura: requiring great skill and agility to be played

bel canto: an easy listening type of singing

capriccio: free, irregular musical composition

castrato: castrated male singer

cavatina: simple melody

cello: larged stringed instrument of the violin family

concert: a public musical performance

diva: famous female singer with air of self-importance

folio: folder containing loose papers, like sheet music

fantasia: free and fantasy-like instrumental composition

forte: to be played strong or loudly

intermezzo: short composition in between main acts or divisions

libretto: small book or text

maestro: master

mandola: type of lute, predecessor to the mandolin

opera: a musical drama

operetta: a “light” or comic opera

piccolo: small flute

piano: type of musical instrument

solo: musical piece played or performed by one individual alone

soprano: highest singing voice

tempo: relative time or pace

viola: a stringed instrument

Science Terms

Italy has produced such notable Italian scientists as Alessandro Volta and Guglielmo Marconi, leading to many Italian terms being adapted to English as well.

granite: a very hard igneous rock

gonzo: weird or unusual

influenza: acute disease known more commonly as the flu

lagoon: shallow pond near larger body of water

lava: molten rock from a volcano

malaria: literally “bad air,” a type of disease usually transmitted by mosquitoes

medico: a doctor, surgeon, or medical student

neutrino: very small neutral particle

pellagra: disease caused by niacin deficiency

peperino: a porous volcanic rock

rocket: self-propelling projectile

torso: trunk of the human body

volcano: a mountain with a vent in the earth’s crust at the top

Other English Words from Italian

Beyond food, music and science, many more Italian words have made their way into English too.

alarm: a warning sound

alert: wide awake, a warning, or to warn for action

arcade: an arched space or a public area with video games

balcony: a platform extending from a building

bankrupt: person unable to pay all debts

ballet: a theatrical type of dance

balloon: inflated bag or ball

ballot: a slip of paper used for voting

bizarre: fantastically strange

brave: valiant and courageous

bronze: a copper and tin alloy

bulletin: a brief statement of news or events

cameo: an engraving technique, or a small role played by a famous performer

carnival: a festival or exhibition

carpet: heavy fabric for covering floors

cartoon: a drawing

cash: physical money

casino: an establishment for gambling

ciao: informal greeting for both “hello” and “goodbye”

facade: front of a building or superficial appearance

fiasco: complete failure

figurine: a small figure or statue of the human form

finale: the last part of a performance

gallery: a room or building for art exhibition

gondola: type of boat from Venice, Italy or an enclosed cabin for transporting up a ski slope

grotesque: unnatural, ugly or absurd in appearance

lotto: a game of chance

Madonna: the Vrigin Mary

magazine: a periodic publication or a place for keeping ammunition

manage: to take charge or direct

musket: infantry gun predating the modern rifle

novel: new and original, or a long fictional story

partisan: supporting one person, party or group

pastel: soft, subdued color

pedal: foot-operated lever

politico: politician

replica: a copy of an original

scenario: sequence of events

sketch: simple drawing

sonnet: a style of poetry, typically consisting of 14 lines

tariff: a tax imposed on imports or exports

umbrella: light cover to protect from rain

vista: a view

Perhaps after reading our list of English words of Italian origin, you will feel like running out for some Italian food or to see an Italian opera. In any case, you can certainly say that you have learned a lot of information about the origin of words!

As you can see from the above list, we owe the Italian language quite a bit of thanks. So many of the words that we use on a daily basis (magazine, brave, and alarm, for example) come from Italian origins. Furthermore, this list does not just point out the words that come from Italy, but also parts of the culture.

Imagine life without pizza or coffee! Learning about the Italian origins of the language also reminds us how many different food items originated in Italy.

You can also read:

Made in Italy, or Italy in brief

John Florio and William Shakespeare