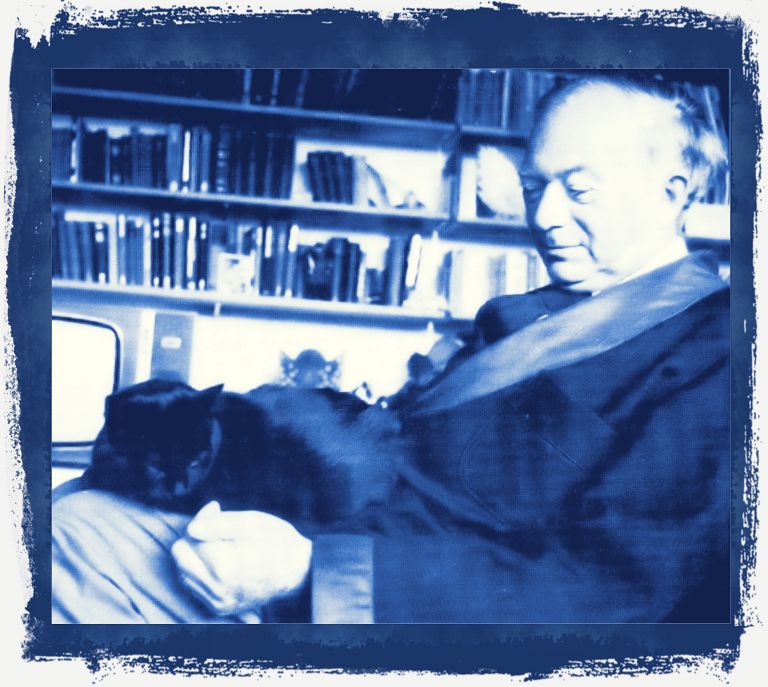

In memory of George Mikes and Tsi-Tsa. This short story is a narrative piece of art which constitutes the last chapter of the book – TSI-TSA The biography of a cat – written by George Mikes and published in London in 1978 by Andre Deutsch, with the pictures of Nicolas Bentley. Nine years later this author died. In 1990 I wrote my university dissertation on him and his literary works, but this book wasn’t included in my thesis, probably because the main argument of my studies was humour and so I left it out of my researches, what’s more, living in Italy, at the time I had not found it. So now, in 2017, I devote this short text to the memory of one of my philosophical and literary master and to his beloved cat Tsi-Tsa, which in Hungarian (cica) means cat.

Carl William Brown’s University Dissertation on George Mikes and the humor phenomenon.

Quadratic Equations

“I DON’T really like writers,” a clever woman-friend once told me, “because they keep observing you, collecting material. They always have an ulterior motive and try to fit you in, at least as a minor character, in their next book.”

“That goes only for novelists,” I replied. “You may go on loving me.”

“How many novels have you written?”

“Three,” I admitted.

Touché, all right. True, I am not totally innocent of these charges. One day — quite recently — I drove out from my garage and Tsi-Tsa jumped away from the wheels in the last moment. As she cannot jump with breathtaking speed and agility, that last moment was a pretty close shave. I got a shock, but when I was driving away I caught myself thinking what a dramatic and unexpected end it would have given this book — on which I was working — if I had killed my own beloved cat. For a moment I actually regretted that I had not run her over.

That passing thought passed very quickly indeed. But there is no getting away from it: it did occur to me. On the other hand, to finish a story with such melodramatic, self-pitying, sentimental rubbish is

not to my taste. I had just read Graham Greene’s new novel, The Human Factor. I quite liked it although I was far from overwhelmed. All the same, I felt fed up with spies and spy-stories. Spies are becoming horrible bores and they are quite unreal. I know they exist, indeed, there are too many of them. Too many spies keep chasing too few secrets. But the people we meet are not spies, they are chartered accountants, grocers, shoemakers, junior executives in machine-tool factories, lawyers and carpenters. The real drama of life is about love, jealousy, betrayal of personal trust, ambition, frustration, humiliation, anger and hatred and not — most definitely not — about murder, spies being chased, spies crossing frontiers disguised as blind men and escaping to Moscow. On reflection, I felt that Tsi-Tsa’s story is, as it happened, more dramatic, more true and more human (if it is humanity one wishes to find in cats) than if it had ended in a dramatic death, with a Freudian murder.

After her return from the hospital, Tsi-Tsa was depressed for weeks. She realised that she could not do things she had been able to do before: she could not jump, she could not run, she could not get out through the window, she had to drag herself most pathetically from one point to another. She sat on the carpet, looked into empty space and lost interest in life. Very occasionally, she ventured out to the patio. Other cats were as cruel as children: they disliked her, were afraid of her disability and blamed her for it. We all feel repelled by cripples, but one of the achievements of civilisation is that we overcome this feeling or at least act as though we had overcome it. Cats – although very civilised in some respects – are not civilised enough in this one and made Tsi-Tsa’s life even more miserable.

It was now that Ginger, the saint, performed a miracle. Tsi-Tsa did not attack him any more, she did not attack anyone. Ginger kept coming in, as before, and Tsi-Tsa watched him with slightly disapproving curiosity. But Ginger, a nobler soul than the rest, a former friend and patron of Beelzebub and other hungry, poor, stray cats, felt that Tsi-Tsa needed friendship and affection. So he gave it to her. He sat with her, was exquisitely polite to her, sought her company and, in a gentle and sophisticated way, even courted her. He wanted no favours from Tsi-Tsa but meant to give her back her self-respect and self- confidence. And he succeeded to a large extent.

Tsi-Tsa got used to Ginger, she seemed to like him now, she was pleased when he came in.

After a few weeks Tsi-Tsa started improving, both physically and mentally. She moved better now; she started coming up to the bedroom, negotiating the steps with increasing ease; she went out into the street, particularly when the sun was shining; she started playing with her favourite piece of string and occasionally even suggested a game of hide and seek.

She could not jump on to my bed or my lap but she pulled herself up with her front claws, thus scratching and wounding my legs and ruining my trousers. But I felt a few small wounds and a few pairs of trousers were a small price to pay for Tsi-Tsa’s happiness.

Her philosophy was clear and I watched it crystallize in her mind. “Very well, I shall have to live a limited life. Better than no life at all. I shall enjoy it. I shall adjust myself to the new circumstances and I shall be happy. Happiness, after all (added Tsi-Tsa) is a gift which you either have or don’t have and it has very little to do with circumstances. I have the gift of happiness.”

I decided to take her to the vet — the same vet with whom we had to break an appointment on the day of the accident. I took Tsi-Tsa to the car in a box, knowing that she was unable to jump out of it. But she did not know that, so she jumped out of the box with the ease of a healthy kitten, hid herself under a car and giggled. There was not a soul in the street to help me. At last a girl came along but she was allergic to cats so she could not help. Then Ginger appeared, went under the car, probably just to say “Hallo” to Tsi-Tsa but she moved out with the old, arrogant disdain. I caught her but we were fifteen minutes late.

The vet said that she had lost the use of the muscles in one of the hind legs. He started twisting her right leg as if Tsi-Tsa had been a toy cat and her leg made of wool. She failed to react, obviously felt nothing.

“To all intents and purposes,” said the vet, “she is a three-legged cat now. I don’t think she will improve although she might a little, very very slowly. But there is no reason why she should not reach a ripe old age.”

But Tsi-Tsa went on improving rather more quickly than anticipated. She can now run at staggering speed, although only for short distances. When getting up on to my lap, she uses her hind legs more and more, and the claws of her front paws less and less. The other day, to my utter amazement, she jumped out of the window, just like in the old days. But she must have been even more amazed by her own reckless audacity than I, because she did not attempt that feat again for a week. Then she leapt again. And again. And today she jumps out whenever she pleases. She cannot leap up to come back. Not yet.

Every morning the newspapers are thrown in at seven o’clock. Then Tsi-Tsa comes up to the bedroom — unless she is already there — jumps on the bed and settles down on my chest in her favourite pose. I stroke her head and try to go back to sleep. But she is purring too loudly and wants to be stroked, so she pushes her head under my hand. After a while I manage to go to sleep again and about half past eight I get up. She goes to the bathroom door and waits for me outside. Then she goes to the steps, lies down on the sixth step (out of seven) and I start to dangle the string in front of her. She makes one or two attempts to catch it but then turns and hurries down to her plates. It is the old, impudent Tsi-Tsa again. She is clearly telling me: “All right, I’m playing this stupid, childish game with the string for your sake as you seem to be so fond of it. But enough is enough.” She gets her breakfast, eats half of it and goes to the door, to be let out. I open the door a few inches and Ginger rushes in like a tiger, leaping across Tsi-Tsa, runs to her plates and eats up what’s left and drinks her milk. Tsi-Tsa looks back in sorrow, shakes her head and goes out. A little later she comes back and then both cats settle down under the table and sleep side by side.

Tsi-Tsa has shaken off her depression, adjusted herself to a new life and accepted her limitations with a kind of wisdom I have not often found in human friends. She cannot solve quadratic equations, knows very little about the later Roman Emperors and has no idea who Chomsky is. Her actual knowledge is limited; her wisdom is vast. When it comes to wisdom, she beats nearly all my friends (the majority of whom cannot solve quadratic equations either, know just as little about the later Roman Emperors as Tsi-Tsa does and have only the faintest idea who Chomsky is).

That’s Tsi-Tsa’s story. Her biography. While writing it, I was told several times by various friends that I was wasting my time.

“Cats come and go. Cats are born and die, leaving little trace behind and very few memories. What does it matter whether they lived or not?”

How true. Cats, in this respect, are just like human beings.

From the book: TSI-TSA, the biography of a cat by George Mikes.

You can also read:

Carl William Brown’s University Dissertation on George Mikes and the humor phenomenon.