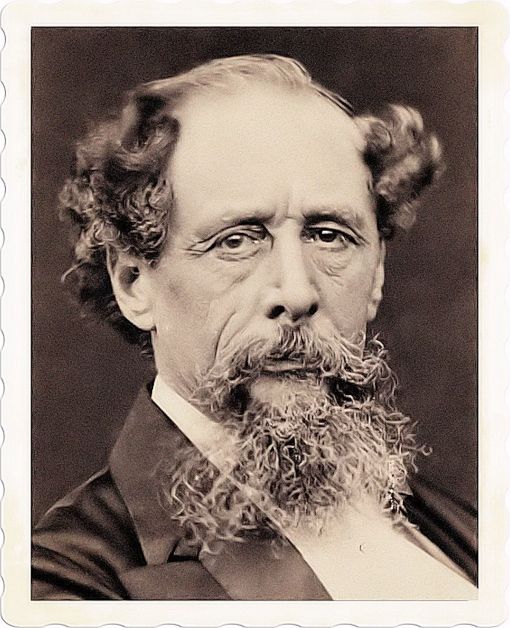

Great Expectations masterpiece, a novel of personal development by Charles Dickens. An analysis of the story and its realization including a piece of the original text and some opinions from the readers.

We think the feelings that are very serious in a man quite comical in a boy.

Charles Dickens

I loved her against reason, against promise, against peace, against hope, against happiness, against all discouragement that could be.

Charles Dickens

Suffering has been stronger than all other teaching, and has taught me to understand what your heart used to be. I have been bent and broken, but – I hope – into a better shape.

Charles Dickens

Her contempt for me was so strong, that it became infectious, and I caught it.

Charles Dickens

Take nothing on its looks; take everything on evidence. There’s no better rule.

Charles Dickens

If you can’t get to be uncommon through going straight, you’ll never get to do it through going crooked. […] live well and die happy.

Charles Dickens

Ask no questions, and you’ll be told no lies.

Charles Dickens

Life is made of so many partings welded together.

Charles Dickens

We need never be ashamed of our tears.

Charles Dickens

Spring is the time of year when it is summer in the sun and winter in the shade.

Charles Dickens

In a word, I was too cowardly to do what I knew to be right, as I had been too cowardly to avoid doing what I knew to be wrong.

Charles Dickens

The broken heart. You think you will die, but you just keep living, day after day after terrible day.

Charles Dickens

Great Expectations was published as a serial novel between September 1860 and August 1861. It is one of the great Victorian novels of personal education and development, since it charts the stages of formation and the changing social and personal influences acting on a young boy. The novel follows the childhood and young adult years of Pip a blacksmith’s apprentice in a country village. He suddenly comes into a large fortune (his great expectations) from a mysterious benefactor and moves to London where he enters high society. He thinks he knows where the money has come from but he turns out to be sadly mistaken.

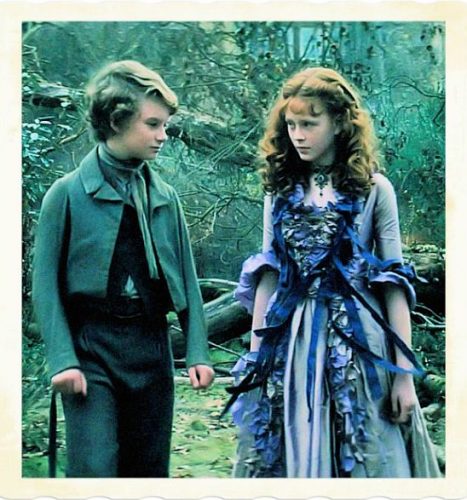

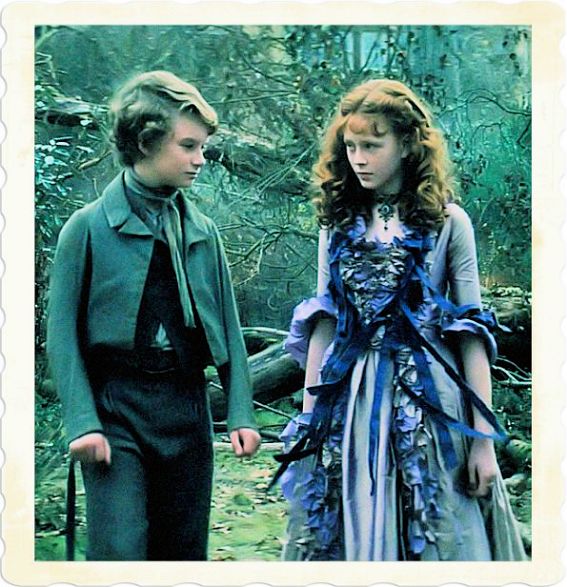

The story also follows Pip’s dealings with Estella, a young woman he adores since his childhood but who cannot return his love. Though this book features the usual gallery of Dickens’s characters, they are less obviously comic than those in The Pickwick Papers, for example. This is in keeping with the sober mood of the novel, which explores two serious themes like ambition and rejected loye. The author studies the effects of the former on love, and observes how the latter can destroy an abandoned lover who in turn poisons other people’s lives in the pursuit of revenge.

The great female character that we analyze is that of Miss Havisham, an eccentric woman who lives in a large, almost derelict house in the town near where young Pip lives. Of the many memorable characters created by Dickens, she is one of the most unforgettable. As a young bride she was abandoned on her wedding day. Now, many years later, she is an ageing woman who never leaves her candle-lit room and has worn only her wedding dress for years. Already a disconcerting figure, she is further magnified because Dickens uses a favourite technique of describing her (through the impressionable eyes of the child Pip, who notices details in her dress and in the room that intensify her strangeness. The stopped clock, the single shoe on the table, the pile of clothes on the dresser suggest that the woman is seriously disturbed and deeply unhappy.

A common criticism of Dickens’s characterization is that it is vivid but superficial. Yet, when Miss Havisham almost boasts that her heart has been broken, with a weird smile and an eager look that create a strong sense of a traumatized inner life, the characterization achieves great psychological depth. Another reason why Miss Havisham is such an unforgettable character is that she appears to have so many associations that go beyond her immediate social identity. The single shoe she wears reminds us that unlike Cinderella’s Prince, her own lover abandoned her. Miss Havisham also has a young ward, an orphan named Estella, who she is bringing up to be a lady. In a way, Miss Havisham is a fairy Godmother to Estella, who is herself a Cinderella figure.

Miss Havisham, however, has become a wicked fairy Godmother, because she is corrupting Estella by turning her into a young woman who will deliberately try to break men’s hearts. When we consider the two children, Estella and Pip, both trapped by Miss Havinsham’s apparent kindness, we might also remember the fairy story of Hansel and Gretel, who are caught in the home of the witch who lives in the house of sugar loaf. This ability to create characters that seem to emerge from the collective imagination prompted the writer G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) to claim that Dickens is not so much a novelist but a mythologist.

Great Expectations is such a popular novel also because readers grow up with it, wrote Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in the Guardian. “It’s probably also why so many of them sympathise with Pip, whose narrative voice involves the perspective of a wide-eyed child coming up against that of his wiser, sadder adult self. Anyone who first reads the story as a child and returns to it in later years is likely to feel a similar mixture of nostalgia and relief. But it isn’t only individual readers who have grown up with Great Expectations. Our culture has too. Dickens once claimed that David Copperfield was his ‘favourite child’ and that Great Expectations was a close second. It’s no coincidence that both novels are about how easily children can be warped or damaged, but of the two it is the shorter, sharper Great Expectations that has aged better.”

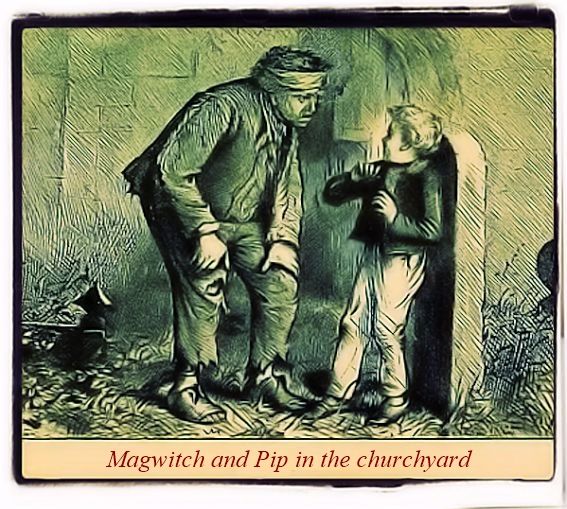

Philip Pirrip, commonly known as “Pip”, is an orphan brought up by his severe sister, the wife of the gentle, humorous, kind blacksmith, Joe Gargery. We first meet the protagonist at the cemetery visiting the grave of his parents. On his way home he is caught by an escaped convict who frightens the little boy into getting him some food and a tool to cut his chains. Later the convict is captured and taken back to a prison ship on the nearby marshes. Some time later, Miss Havisham arranges for Pip to visit her regularly to serve as a “companion” to Estella. Miss Havisham is half-crazed after the desertion of her fiancé just before the wedding ceremony. In a spirit of revenge she has brought up the girl Estella to use her beauty as a means of torturing men. Pip falls in love with Estella and becomes ashamed of his social position.

Charles Dickens’s novel Great Expectations is a novel of development. I will try to highlight the way this theme is conveyed in an excerpt which signals an important crisis in the protagonist’s life. The passage describes Pip’s first visit to Miss Havisham. The first part of the passage is taken up with the description of the room and its occupant, an old lady dressed in a faded bridal dress. It is a large room, lighted with wax candles. There’s a clock. There are bridal articles scattered all over. The lady is wearing only one shoe. She is also wearing a watch, stopped at twenty to nine, like the clock on the wall.

The second part of the passage introduces Estella, Miss Havisham’s ward, whom Pip is supposed to play with. As they are about to play, Pip suddenly understands that nothing has changed in the room since when the clock stopped. Meanwhile, as they play, Estella treats Pip disdainfully and he would like to go home. However, he stays and plays the game. The episode is told from the point of view of Pip, so the reader sees everything through the eyes of a child. We share his emotions when he slowly begins to realize some shocking truths about Miss Havisham and when, as he plays cards with Estella, he feels ashamed of himself for the first time in his life.

He describes Estella’s contempt as “infectious”, a word that pervades the place with a sense of unhealthiness, principally mental. Which brings me back to the character of Miss Havisham. Every detail contributes to build her strange personality: the absence of natural light and air; and the presence of the past, highlighted by the clock. Most of all, the colour white, which is usually associated with a youthful bride. But Miss I Havisham’s age and the faded white provide a strong contrasting effect, suggesting the whiteness of bones, dust and death. Miss Havisham tells Pip that she is broken-hearted, and Pip realizes that something dreadful must have happened to her. Seen through the eyes of a child, Miss Havisham appears as a wicked godmother.

The fairy-tale atmosphere, is reinforced by the sense of confinement created by the lack of natural light, which suggests that the two children are imprisoned, just as Hansel and Gretel were in the witch’s house. As a matter of fact, when Pip enters Miss Havisham’s room, he steps into a world that is totally, different from his childhood world. It is in this room that Pip falls in love for the first time, and first learns about class difference. Therefore the passage marks a turning point in the boy’s life, which is particularly important in a novel of development. Everything that happens to Pip from now on, from his future life as a gentleman to the ambiguous ending of his love story with Estella, will be marked by the impressions he receives in the episode described here.

A Broken Heart

I entered, therefore, and found myself in a pretty large room, well lighted with wax candles. No glimpse of daylight was to be seen in it. It was a dressing-room, as I supposed from the furniture, though much of it was of forms and uses then quite unknown to me. But prominent in it was a draped table with a gilded looking-glass, and that I made out at first to be a fine lady’s dressing-table.

Whether I should have made out this object so soon, if there had been no fine lady sitting at it, I cannot say. In an arm-chair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials – satins, and lace, and silks – all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil dependent from her hair, and she had bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white. Some bright jewels sparkled on her neck and on her hands, and some other jewels lay sparkling on the table. Dresses, less splendid than the dress she wore, and half-packed trunks, were scattered about. She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on – the other was on the table near her hand – her veil was but half arranged, her watch and chain were not put on, and some lace for her bosom lay with those trinkets, and with her handkerchief, and gloves, and some flowers, and a Prayer-Book, all confusedly heaped about the looking-glass.

It was not in the first moments that I saw all these things, though I saw more of them in the first moments than might be supposed. But I saw that everything within my view which ought to be white, had been white long ago, and had lost its lustre, and was faded and yellow. I saw that the bride within the bridal dress had withered like the dress, and like the flowers, and had no brightness left but the brightness of her sunken eyes. […]

“Who is it?” said the lady at the table.

“Pip, ma’am.”

“Pip?”

“Mr Pumblechook’s boy, ma’am. Come – to play.”

“Come nearer; let me look at you. Come close.”

It was when I stood before her, avoiding her eyes, that I took note of the surrounding objects in detail, and saw that her watch had stopped at twenty minutes to nine, and that a clock in the room had stopped at twenty minutes to nine.

“Look at me,” said Miss Havisham. “You are not afraid of a woman who has never seen the sun since you were born?”

I regret to state that I was not afraid of telling the enormous lie comprehended in the answer, “No”.

“Do you know what I touch here?” she said, laying her hands, one upon the other, on her left side.

“Yes, ma’am.” […]

“What do I touch?”

“Your heart.”

“Broken!”

She uttered the word with an eager look, and with strong emphasis, and with a weird smile that had a kind of boast in it. Afterwards, she kept her hands there for a little while, and slowly took them away as if they were heavy.

“I am tired”, said Miss Havisham. “I want diversion, and I have done with men and women. Play.’ […]

Miss Havisham calls Estella, so that Pip can play cards.

Miss Havisham beckoned her to come close, and took up a jewel from the table and tried its effect upon her fair young bosom and against her pretty brown hair. “Your own, one day, my dear, and you will use it well. Let me see you play cards with this boy.”

“With this boy! Why, he is a common labouring-boy!”

I thought I overheard Miss Havisham answer – only it seemed unlikely – “Well? You can break his heart.”

“What do you play, boy?” asked Estella of myself with the greatest disdain.

“Nothing but beggar my neighbour, miss.”

“Beggar him”, said Miss Havisham to Estella. So we sat down to cards.

It was then I began to understand that everything in the room had stopped, like the watch and the clock, a long time ago. I noticed that Miss Havisham put down the jewel exactly on the spot from which she had taken it up. As Estella dealt the cards, I glanced at the dressing-table again and saw that the shoe upon it had never been worn. I glanced down at the foot from which the shoe was absent, and saw that the silk stocking on it, once white, now yellow, had been trodden ragged. Without this arrest of everything, this standing still of all the pale decayed objects, not even the withered bridal dress on the collapsed form could have looked so like grave-clothes, or the long veils so like a shroud. […]

“He calls the knaves, Jacks, this boy!” said Estella with disdain, before our first game was out.

“And what coarse hands he has. And what thick boots!”

I had never thought of being ashamed of my hands before; but I began to consider them a very indifferent pair. Her contempt for me was so strong, that it became infectious, and I caught it.

She won the game, and I dealt. I misdealt, as was only natural, when I knew she was lying in wait for me to do wrong; and she denounced me for a stupid, clumsy labouring-boy.

“You say nothing of her,” remarked Miss Havisham to me, as she looked on.

“She says many hard things of you, but you say nothing of her. What do you think of her.

“1 don’t like to say, ” I stammered.

“Tell me in my ear,” said Miss Havisham, bending down.

“I think she is very proud,” I replied in a whisper.

“Anything else?”

“I think she is very pretty.”

“Anything else?”

“I think she is very insulting.” (She was looking at me then, with a look of supreme aversion).

“Anything else?”

“I think I should like to go home.”

“And never see her again, though she is so pretty?’

“I am not sure that I shouldn’t like to see her again, but I should like to go home now.”

“You shall go soon.” said Miss Havisham aloud. “Play the game out.”

(From Great Expectations, Ch. VIII, Charles Dickens, The Wordsworth Classics, 1992.)

How the story ends

After some time Pip leaves Miss Havisham’s house and becomes apprenticed as a blacksmith to his brother-in-law, Joe. Some years later, money and expectations of more wealth come to Pip from a mysterious source, which he believes to be Miss Hivisham. He goes to London where he learns to become a gentleman and grows ashamed of his humble connections. But he has to revise his opinions when he learns that his actual benefactor is the escaped convict, Magwitch whom he had helped as a boy. By coming back to England to see Pip and thank him, the criminal risks death by hanging. Moved by Magwitch’s love, loyalty, and generosity, Pip determines to help him escape the country.

But Magwitch is discovered and taken as they try to escape to France by boat. Wounded in the pursuit, the ex-convict dies in the prison hospital. Pip also loses his other surrogate parent because Miss Havisham dies in a fire started by one of her eternally burning candles. Pip also learns from his lawyer, Jaggers, that Estella is Magwitch’s daughter Estella however, has married a rich man, by whom she is ill-treated, though he soon dies. Disillusioned by his experiences, Pip leaves England and devotes himself to work abroad. On his return to England he meets Estella again. She too has learnt her lesson.

The two endings of Great Expectations

Most paperback editions of Great Expectations include the original ending of the novel, but it is reproduced here in case it is not included in the copy you have. In the original text in Ch. 59; Vol. 3, Ch. 20), after Pip’s words ‘all gone by, Biddy, all gone by!’ came the following paragraph:

It was four years more, before I saw herself. I had heard of her as leading a most unhappy life, and as being separated from her husband who had used her with great cruelty, and who had become quite renowned as a compound of pride, brutality, and meanness. I had heard of the death of her husband (from an accident consequent on ill-treating a horse), and of her being married again to Shropshire doctor, who, against his interest, had once very manfully interposed, on an occasion when he was in professional attendance on Mr. Drummle, and had witnessed some outrageous treatment of her. I had heard that the Shropshire doctor was not rich, and that they lived on her own personal fortune.

I was in England again, in London, and walking along Piccadilly with little Pip when a servant came running after me to ask would I step back to a lady in a carriage who wished to speak to me. It was a little pony carriage, which the lady was driving; and the lady and I looked sadly enough on one another.

“I am greatly changed, I know, but I thought that you would like to shake hands with Estella too, Pip. Lift up that pretty child and let me kiss it!” (She supposed the child, I think, to be my child.)

I was very glad afterwards to have had the interview; for, in her face and in her voice, and in her touch, she gave me the assurance, that suffering has been stronger than Miss Havisham’s teaching, and had given her a heart to understand what my heart used to be.

Dickens allowed himself to be persuaded – among others by his friend and fellow-novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton – that this ending would not be acceptable to his readers and that he should write something more optimistic.

Pip addresses Estella

“We are friends,” said I, rising and bending over her, as she rose from the bench.

“And will continue friends apart”, said Estella.

I took her hand in mine, and we went out of the ruined place; and, as the morning mists had risen long ago when I first left the forge, so the evening mists were rising now, and in all the broad expanse of tranquil light they showed to me, I saw no shadow of another parting from her.

Read the two endings carefully and try to answer these questions:

Which of the endings comes closer to your own expectations as you came towards the end of the book?

Which of the endings seems to you the more probable?

If Dickens had retained the first ending, what difference would it make to your reading of the novel?

Do you think that the second ending implies that Pip and Estella are happily reunited and get married? Give reasons for and against this view.

Do you think that the narrative sounds as though it is written by a man who is happily married to the woman of his dreams?

Pip’s place in readers’ affections was also attributed to the wealth of film and television adaptations which have been made of the novel over the years. Last but not least, even if perhaps the author himself might have preferred David Copperfield, the Guardian readers some years ago voted for Great Expectations as their favourite Charles Dickens novel. Pip’s adventures won 24.9% of the reader poll, well ahead of the second-placed Bleak House with 16.9%. David Copperfield, which Dickens called his “favourite child”, was third with 9.2% of the vote.

From its famous opening in the graveyard, when the orphan Pip first encounters the shackled convict Magwitch, “a fearful man, all in coarse gray, with a great iron on his leg”, through his meetings with the bitter Miss Havisham and the cold Estella, and his rise through society thanks to a mysterious benefactor, Great Expectations is, said one the voter, “not only – as others have observed – formally the most ingenious of the novels – but perhaps Dickens’s most morally angry work”. And to such comment I would also add that this novel is one of the most poetic and psychologically impressive written by Dickens, a writer that has certainly taught to everyone the real and deep value of the literary genial work of art.

Other Dickens novels and the result of the most liked by the readers of the Guardian:

A Christmas Carol 7.4%

A Tale of Two Cities 8.7%

Barnaby Rudge 4.6%

Bleak House 16.9%

David Copperfield 9.2%

Dombey and Son 1.9%

Great Expectations 24.9%

Hard Times 2.9%

Little Dorrit 3.6%

Our Mutual Friend 6.5%

Oliver Twist 4.6%

Martin Chuzzlewit 1%

Nicholas Nickleby 1.8%

The Mystery of Edwin Drood 0.8%

The Old Curiosity Shop 1.2%

Other books by Charles Dickens