Carl William Brown on Humour, some quotes, aphorisms, ideas, thoughts and reflections to enrich this short essay on one of the most nice human phenomenon.

Since every religion was able to make me laugh, I decided that after all humour might have become my own true religion.

Carl William Brown

I don’t believe in God, but I have got a magical sense of humour.

Carl William Brown

All art is quite useless and so it is the universe.

Carl William Brown

The first mistake of art is to assume that it’s serious.

Lester Bangs

Imagination was given man to compensate for what he is not, and a sense of humor to console him for what he is.

Francis Bacon

The world is destined to become even more comical; that is why humorists are the real precursors of our future civilisation.

Carl William Brown

A church of England man abhors the humour of the age, in delighting to fling scandals upon the clergy in general; which, besides the disgrace to the reformation, and to religion itself, cast an ignominy upon the kingdom that it doth not deserve.

Jonathan Swift on the Sentiments of a Church of England man.

Humor is a means of obtaining pleasure in spite of the distressing effects that interface with it.

Sigmund Freud

Humour is as dead as Chaplin; Keaton and Lloyd-films are. It cannot be rescued; it cannot survive. But it can resurrect. This age cannot be the purveyor of humour; but it can – and will, be the proper subject of it.

George Mikes

Humour, as we shall see, has many ingredients, some of them not very attractive. But two of the essential (and attractive) are wisdom and self-mockery. This age is not wise; and it cannot afford self-mockery.

George Mikes

I do believe with Freud, that humour is one of the highest psychical achievement and that it has certain redeeming features which put it among the great gifts of humanity. It is not all snow-white; it is not one hundred per cent beauty and bliss but, warts and all, it deserves our respect and affection.

George Mikes

As I shall explain later, cowardice is one of the dominant forces and motives of human development and, on the whole, it is a beneficial and commendable influence. Cowardice is the foundation stone of all religions: it is also the foundation stone of humour.

George Mikes

L’humour intéressant surtout les régions supérieures (c’est-à-dire conscientes) du rire, sa phase critique est intellectuelle et nous l’appellerons ironie.

Robert Escarpit

Allusion in the very broadest sense is never absent from humour discourse; always there is some fact of shared experience, some circumstance implicit in the common culture, to which participants in a conversation may confidently allude. For families, friends, neighbours, colleagues, there is a generic knowledge of the affairs of the day – of politics, of social question, of sports and entertainments, of current notions and phraseology. Such knowledge informs a good deal of what we say to each other, making its point even when its presence is veiled.

Walter Nash

Humor is by far the most significant activity of the human brain.

Edward De Bono

Humor is something that thrives between man’s aspirations and his limitations. There is more logic in humor than in anything else. Because, you see, humor is truth.

Victor Borge

A joke is an epigram on the death of a feeling.

Author Unknown

Good humor is one of the best articles of dress one can wear in society.

William M. Thackeray

Humor is just another defense against the universe.

Mel Brooks

No mind is thoroughly well organized that is deficient in a sense of humor.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

People of humor are always in some degree people of genius.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Humor is a serious thing. I like to think of it as one of our greatest earliest natural resources, which must be preserved at all cost.

James Thurber

Humor has been a fashioning instrument in America, cleaving its way through the national life, holding tenaciously to the spread elements of that life. Its mode has often been swift and coarse and ruthless, beyond art and beyond established civilization. It has engaged in warfare against the established heritage, against the bonds of pioneer existence. Its objective – the unconscious objective of a disunited people – has seemed to be that of creating fresh bonds, a new unity, the semblance of a society and the rounded completion of an American type.

Constance Rourke

As far as I am concerned true humor should always be a kind of black humor. See for instance Luis Bunuel, Canetti, Bréton, Cioran, the Dadaists, Picasso, the Surrealists, etc. (see also articles on evil, aggression, revolt, self-realization, crime, new crime, and so on…).

Carl William Brown

As Blake said the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God, and humour without any doubt means indignation towards the follies of the world, sarcastic indignation against human vanity, his authority and his stupidity. We can also consider Humor as a form of revenge through which we can get even of the abuses supported without breaking the law. Humor, which is one of the highest activity of the human brain, as Freud said, is thus a means that helps us to live better and to endure our distressing reality. As a matter of fact, it is a good therapy and a way of teaching us something through a lively approach.

In ancient medical theory there were four principal “humours” in the human body (phlegm, blood, choler and black bile) and the bad balance of these elements caused illness, while an exact balance made a compound called “good humour”! The concept of “humors”, also spelled “humor” (i.e. chemical systems regulating human behaviour) became more prominent from the writing of medical theorist Alcmaeon of Croton (C. 540–500BC). His list of humours was longer than just four liquids and included fundamental elements described by Empedocles, such as water, air, earth, etc.

Some authors suggest that the concept of “humours” may have origins in Ancient Egyptian medicine or Mesopotamia, though it was not systemized until ancient Greek thinkers. The word “humour” is a Latin translation of the Greek word “chymos” (literally juice or sap, metaphorically flavor) meaning “liquid” or “fluid”. However much earlier than this, ancient Indian Ayurveda medicine had developed a theory of three humors, which they linked with the five Hindu elements, earth, water, fire, air and sky.

Hippocrates is the one usually credited with applying this idea to medicine. In contrast to Alcmaeon, Hippocrates suggested that humours are the vital bodily fluids, such as blood, yellow bile, phlegm and “black bile” (he probably referred to blood composites in patients with bleeding internal organs). Alcmaeon and Hippocrates expressed that an extreme excess or deficiency of any of the humours bodily fluid in a person might be a sign of illness.

Hippocrates and then Galen suggested that a moderate imbalance in the mixture of these fluids produces temperament (behavioural) type and feauters, therefore in one of the treatises attributed to Hippocrates, On the Nature of Man, this theory is described as follows: “The Human body contains blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. These are the things that make up its constitution and cause its pains and health. Health is primarily that state in which these constituent substances are in the correct proportion to each other, both in strength and quantity, and are well mixed. Pain occurs when one of the substances presents either a deficiency or an excess, or is separated in the body and not mixed with others.”

This medical theory, still current in the European Middle Ages and later, explained that the variant mixtures of these humours in different persons determined their “complexions,” or “temperaments,” their physical and mental qualities, and their dispositions. The ideal person had the ideally proportioned mixture of the four; a predominance of one produced a person who was sanguine (Latin sanguis, “blood”), phlegmatic, choleric, or melancholic.

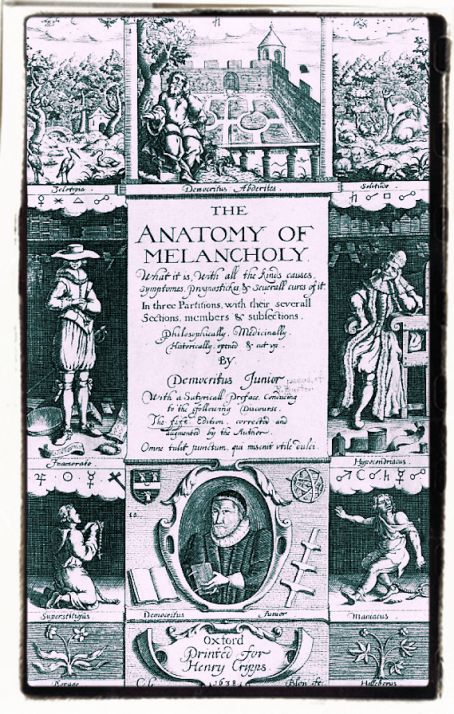

In his work The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in 1621 and then revised five times, Robert Burton defined his subject as follows: “Melancholy, the subject of our present discourse, is either in disposition or in habit. In disposition, is that transitory Melancholy which goes and comes upon every small occasion of sorrow, need, sickness, trouble, fear, grief, passion, or perturbation of the mind, any manner of care, discontent, or thought, which causes anguish, dulness, heaviness and vexation of spirit, any ways opposite to pleasure, mirth, joy, delight, causing forwardness in us, or a dislike. In which equivocal and improper sense, we call him melancholy, that is dull, sad, sour, lumpish, ill-disposed, solitary, any way moved, or displeased. And from these melancholy dispositions no man living is free, no Stoic, none so wise, none so happy, none so patient, so generous, so godly, so divine, that can vindicate himself; so well-composed, but more or less, some time or other, he feels the smart of it. Melancholy in this sense is the character of Mortality… This Melancholy of which we are to treat, is a habit, a serious ailment, a settled humour, as Aurelianus and others call it, not errant, but fixed: and as it was long increasing, so, now being (pleasant or painful) grown to a habit, it will hardly be removed.”

The book is presented as a medical textbook in which Burton applies his vast and varied learning, in the scholastic manner, to the subject of melancholia (which includes, although it is not limited to, what is now termed clinical depression). Nonetheless The Anatomy of Melancholy is much more a work of literature than a scientific or philosophical text, and Burton addresses far more than his stated subject. In fact, the Anatomy uses melancholy as the lens through which all human emotion and thought may be scrutinized, and virtually the entire contents of a 17th-century library are used to achieve this goal, therefore resulting fully encyclopedic in its range of reference.

In order to attack his stated subject, Burton drew from nearly every science of his day, including psychology and physiology, but also astronomy, meteorology, and theology, and even astrology and demonology. Much of the book consists of quotations from various ancient and medieval medical authorities, beginning with Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen. Hence the Anatomy is filled with more or less pertinent references to the works of others. A competent Latinist, Burton also included a great deal of Latin poetry in the Anatomy, and many of his inclusions from ancient sources are left untranslated in the text.

Coming back to our “humour” theory, each complexion had specific characteristics, and the words carried much weight that they have since lost: e.g., the choleric man was not only quick to anger but also yellow-faced, lean, hairy, proud, ambitious, revengeful, and shrewd. By extension, “humour” in the 16th century came to denote an unbalanced mental condition, a mood or unreasonable caprice, or a fixed folly or vice and the term was usually associated with medical description and illnesses, as the following quotes from The Dictionary of the English Language by Samuel Johnson’s published in 1755 clearly demonstrate:

A medicine that, by the softness or porosity of its parts, either causes the asperities of pungent humours, or dries away superfluous moisture in the body.

Quincy, John

The wearing away of the natural mucus, which covers the membranes, particularly those of the stomach and guts, by corrosive or sharp medicines, or humours.

Quincy, John

The seventh cause is abstersion; which is plainly a scouring off, or incision of the more viscous humours, and making the humours more fluid, and cutting between them and the part; as is found in nitrous water, which scoureth linen cloth speedily from the foulness.

Bacon, Francis

Great evacuations, which carry off the nutritious humours, depauperate the blood.

Arbuthnot, John

A looseness wherein very ill humours flow off by stool, and are also sometimes attended with blood.

Johnson, Samuel

The ancient writers distinguished putrid fevers, by putrefaction of blood, choler, melancholy, and phlegm; and this is to be explained by an effervescence happening in a particular cacochymical blood.

Floyer, John On the Humours.

Many hysterical women are sensible of wind passing from the womb.

Floyer, John On the Humours.

In modern times, however the concept of humor has enlarged enormously and nowadays we talk about humor in literature as well as in everyday life to indicate not only a genre of writing but also a particular mood or character to face our existence and overcome the different anxieties of its burdens!

Humor is the feeling of the contrary, while the comic is the observation of it, said Pirandello in his essay on Humor, but nowadays we can consider humor as an hypernymic word that incorporates other styles and ways of oral and written expression such as comedy, satire or parody, and that makes use of all the linguistic and rhetorical devices of our tradition, such as irony, sarcasm, metaphors, puns and other tropes or schemes. In any case we associate humor with what makes us laugh or that evokes mirth, pleasure or strong as well as soft criticism towards the vices of the human kind.

Someone point out that humor is a nihilistic approach to life and that it tend to destroy and reject all established codes of values and morality, but this way to destroy is nothing but a way to create a new and healthier human behaviour, as Bacone or Eliot taught us! Of course we have to understand the different ways of fantastical writing and thus we have also to come to terms with jokes production and nonsensical literature, but in the long run all this will help us to better appreciate the ineffectual, ridiculous, even comical, meaning of our existence and so at last we will learn to understand better also its final essence!

A joke from Jewish circles (published in 1981) celebrating Jewish intelligence, Gentile stupidity, and Jewish fraud, runs like this:

“On a train in czarist Russia, a Jew is eating a whitefish, wrapped in paper. A Gentile, sitting across the aisle, begins to taunt him with various anti-Semitic epithets. Finally, he asks the Jew, ‘What makes you Jews so smart?’

‘All right,’ replies the Jew, ‘I guess I’ll have to tell you. It’s because we eat the head of the whitefish.’

‘Well, if that’s the secret,’ says the Gentile, ‘then I can be as smart as you are.’

‘That’s right,’ says the Jew, ‘And in fact, I happen to have an extra whitefish head with me. You can have it for five kopecks.’

The Gentile pays for the fish head and begins to eat. An hour later the train stops at a station for a few minutes. The Gentile leaves the train and comes back.

‘Listen, Jew,’ he says, ‘You sold me that whitefish head for five kopecks. But I just saw a whole whitefish at the market for three kopecks.’

‘See,’ replies the Jew, ‘You’re getting smarter already.'”

And now a bit of German humour.

Humor is not a mood but a way of looking at the world. So if it is correct to say that humor was stamped out in Nazi Germany, that does not mean that people were not in good spirits, or anything of that sort, but something much deeper and more important.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Some men are very good humorist, but they lack the ability and the responsability to recognize it. Take Hitler for example. When the Nazis came to power in January 1933, the party only won 37 percent of the vote across Germany. In the Reichstag, the German parliament, the National Socialists only controlled a third of the seats when Hitler came to power. When they held another election two months later, after crushing other parties and quieting opposition, they still only won 43 percent of the vote and less than half of the Reichstag. So it’s safe to say that not every German was huge supporter of the Nazi party and its leadership. But after a while, criticizing the government became more and more hazardous to one’s health. How does a population who can’t openly object to their government blow off the built-up popular anger among friends? With jokes.

The end became apparent in jokes long before the reality of the situation.

Hitler and his chauffeur are driving through the country, when there’s a crash. They ‘ve run over a chicken. Hitler says to his chauffeur: “I ‘ll tell the farmer. I “m the Führer He’ll understand.” Two minutes later, Hitler comes up rubbing his behind from where the farmer kicked him in the ass. The two men drive on, and a short time later there’s another crash. This time they’ve run over a pig. Hitler tells his chauffeur: ”You go in this time.” The chauffeur obeys and after an hour he comes out of the farmer’s house, and when he does, he’s drunk and is carrying a basket full of sausages and other gifts. Hitler can’t believe his eyes. ”What did you tell the farmer? ” he asks. The chauffeur says: “Nothing special. I just said, ‘Heil Hitler, the swine is dead.'”

You can find out very interesting books, including The anatomy of melancholy at this link.

Carl William Brown’s University Dissertation on Humour and George Mikes (My Ko-fi Shop)

To make a good healthily laugh you can also visit the following pages!